Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 8)

Section 5 Sugar, Rum, and Slaves (cont'd)

(Plantation owner’s estate: St. Nicholas Abbey, located in the parish of St. Peter, Barbados, was built around the year 1660. It is partly open to visitors now with a rum distillery on the grounds.)

Appearance of Plantocrats

The development of the colony of Barbados expanded rapidly due to the success of the sugar industry, which was supported by slave labor.

It is said that around the year 1660, most of the thick forests on the island were cut down and turned into sugarcane fields, and the general appearance of the island today turned into the current landscape. A reason why rapid development and deforestation of the island occurred is that unlike other Caribbean islands, Barbados did not have any dangerous mountainous areas; it was flat with the occasional hill which made it easy to clear the land to make way for sugarcane fields. Additionally, the small island's terrain aided in keep track of and watching over the slaves, leaving them with limited places to escape to (note 1).

The steadily growing sugar export business made Barbados, for a time, Britain’s most profitable colony during the later 17th century. The streets of Bridgetown, where the shipping port was located, began to be filled with English-style buildings, sugar storehouses and businesses, garnering the nickname “Little England”.

The term “Sugar Revolution” is used to described the phenomenon of the various Caribbean islands focusing their industry on sugar production. Some plantation owners who were able to gain extreme wealth were called the “plantocrats” (plantation aristocrats). They had hundreds of slaves working the fields, and lived lavishly in mansions they had built for them and their family. They made trips in glory to their motherland England, sending their children back to England for higher-level education.

The development of the island’s economy led in part to the white ruling class’s stratification; according to accounts written by Richard Ligon in 1657, there were 36,600 whites including 11,100 small landowners in Barbados in 1645, a few years before sugar exporting came into full speed. However, this situation had completely changed: later on large landowners started to buy up the smaller parcels of land in order to gain more profit from the sugarcane industry by increasing their plantation size. According to a record, in 1667, 745 families owned most of the island’s land, and from 1680 for the next 100 years, more than half of the island’s land was owned by less than 100 families.

The stratification of the ruling class led to the outflow of the white population during the second half of the 17th century. Those who left were mainly small-scale farmers who were late getting on the bandwagon of the sugar revolution as well as indentured servants whose term was up and had trouble either finding land or decent work and fell into poverty. They went in search of a new land, and ended up in other parts of the Caribbean such as Jamaica and Surinam, as well as up the eastern coast of North America to the British colonies of North and South Carolina, Virginia, and those of New England (note 2). This is how the demographics in Barbados shifted to create a reign of the minority white population over the absolute majority Black slave population.

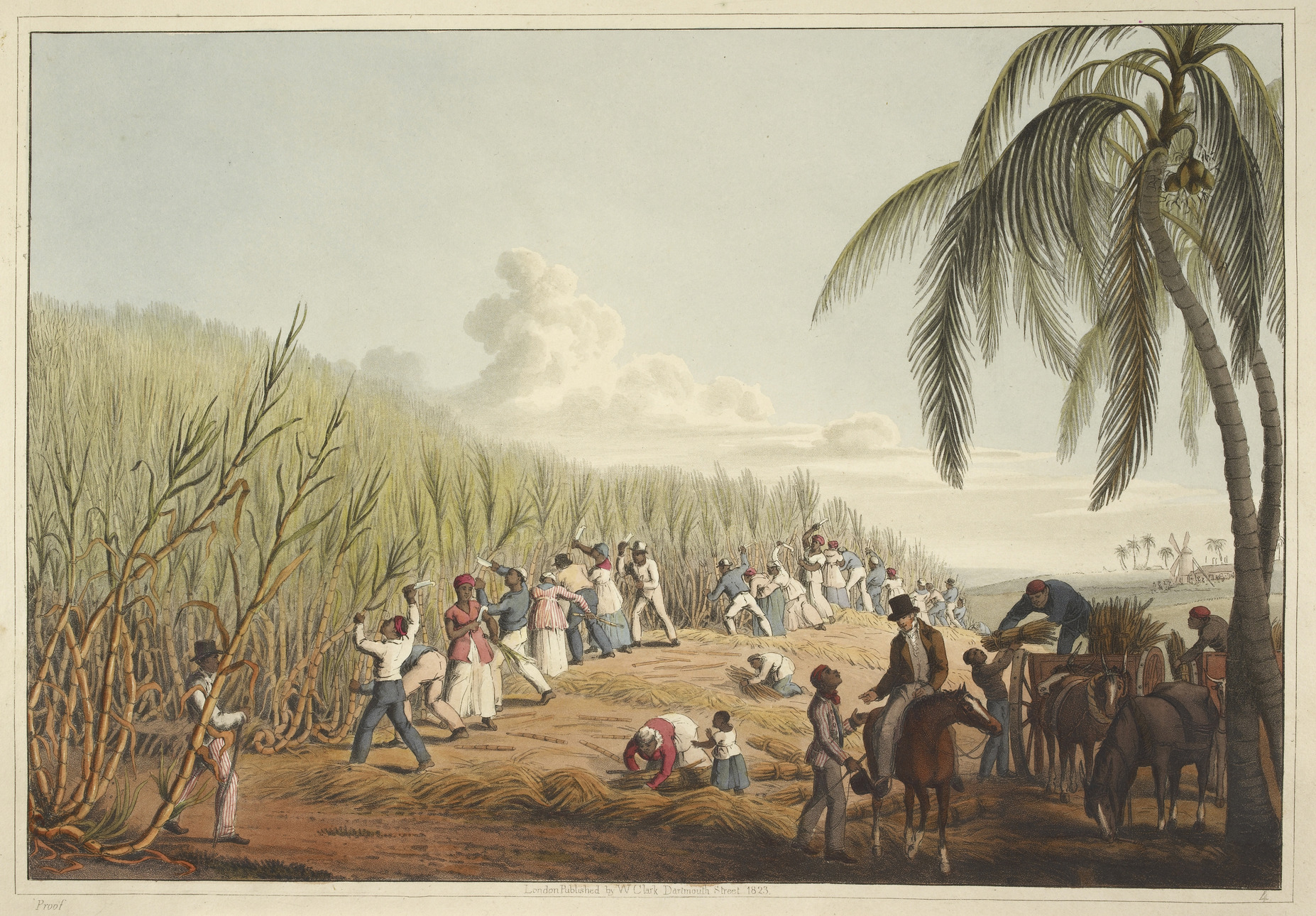

(Slaves used on sugarcane plantations)

The demand for slave labor on plantations continued to increase. However, from the end of the 17th century into the 18th century England began to monopolize the Atlantic slave trade, pushing away other competing nations. This allowed Barbados’ plantation owners to be free of worries of potential lack of slave labor for their sugarcane fields.

In 1672, King Charles II of England issued a royal charter founding the Royal African Company (RAC). The Duke of York, Charles’ younger brother who later on became King James II, was put in charge of the company. Although not directly stated in its name, the company’s main business was trafficking slaves to England’s North American and Caribbean colonies from the west coast of Africa. It is estimated that over 100,000 slaves were abducted from Africa during the first 30 years from the RAC’s foundation. RAC was England’s government-run slave trade enterprise (note 3).

The English traders brought cotton products from England and traded them for slaves on Africa’s west coast, then shipped them to the “New World”; the ships sailed back to England stocked full of sugar, rum, and raw cotton. This triangular trade generated enormous revenue for England, boosting its status from nothing more than a middle power to one of the strongest in Europe.

Liverpool, birthplace of the Beatles centuries later, prospered due to the slave-shipbuilding industry as well as being the port where the ships would leave from and come back to after their slave trading business across the ocean. The city of Manchester-today known for its soccer club, was also a city that profited greatly from their cotton products in exchange for slaves in Africa. Ultimately the wealth generated from the exploitation of slave labor pooled in London, created the base of the future world power city.

On the other hand, the Dutch, who at one point took the lead over England in the slave trade, lost the Anglo-Dutch wars (1652-54, 65-67, 72-74) which spurred from England’s introduction in 1651 of the Navigation Law (reference Section 3: The Island Tossed about by the English Civil War) and contention over who controlled the seas. After their loss, the Dutch’s power on the seas started to wane.

Following the wars, the next emerging obstacle to England’s domination on the Caribbean front was France under the Bourbon Dynasty. It should be mentioned, just to make sure, that England was not the only country to ruthlessly reap in wealth from the slave trade; France was equally cutthroat in amassing revenue. In addition to taking the western half of the island of Hispanola away by force from Spain and creating the colony of Saint-Domingue (later to become Haiti), France also colonized the islands of Guadalupe, Martinique and others. The French cities of Bordeaux, Nantes, Le Havre are examples of port towns that developed due to the slave trade (note 4).

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) solidified England’s hold on the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Spain’s gradually diminishing power fell even further with the Hapsburg Family’s rule coming to an end in 1700. France’s “Sun King” Louis XIV used his blood relationship to place his grandson as the next King of Spain. England, the Netherlands, Prussia, Austria, as well as others intervened, igniting The War of the Spanish Succession. In the end, the Treaty of Ultrecht paved the way for England as one of the wining parties, to considerably expand its overseas territory. Moreover, a supplemental clause in the Treaty gave England the right (“asiento”) to carry African slaves to Spain’s colonies in the ‘New World’, clinching England’s total control over the slave trade and its revenue.

In 1707 during the War of Spanish Succession, the Acts of Union officially united the two separate kingdoms of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain. This was a big step forward to eventually becoming the British Empire-the ruling power of the world.

-Slaves’ Arrival at the Port-

Let’s turn our attention back to Barbados.

African slaves, treated like livestock, were packed tight onto slave ships to Barbados. Those who survived the voyage were shackled and lined up at the slave market in the Port of Bridgetown, where buyers would then come and “appraise” the men and women. Oil was rubbed over their bodies in order to make them look strong and healthy; the buyers would touch their bodies to check the amount of muscle, look at their teeth to check their health condition, valuing them in order to make sure that they did not purchase a “defective product”.

Barbados is located in the most eastern position of all the Caribbean islands-in other words it is the closest in distance to Africa of the Caribbean region, rendering it the hub of the African Slave Trade, and a transfer point where many slaves would be “re-exported” to other colonies.

As previously mentioned, slaves sold to plantations had a life of harsh treatment awaiting them. It is only natural to want to run away or act out in violence against their treatment. However, if a slave who ran away happened to be caught, punishments included whippings, hot iron brandings, cutting of leg tendons, and in the worst of cases death.

These types of punishments were performed in front of the other slaves so as to discourage others from doing the same by instilling fear of such brutal abuse. Needless to say, this was an effect method in deterring unwanted behavior. The slaves must have been trembling in fear, unable to summon the willpower to rebel against the whites.

The white ruling class did not use the blessed teachings of the Bible, nor the discourses of the Enlightenment then becoming popular throughout Europe and England. The simple method of control through fear and violence was used to keep the much larger slave population in line. Use of this card by the civilization of Western Europe-hypo-critical double standards applied to the outside world for their benefit-can be frequently seen throughout world history.

(Current Port of Bridgetown. Where cruise ships traveling around the Caribbean now was once a hub for the Atlantic Slave Trade as well as used for exporting sugar and rum.)

Despite the abusive oppression, the first slave uprising in Barbados occurred as early as 1675. To be more precise, it was being planned.

This revolt was called “Cuffee’s Conspiracy”, named after Cuffee, the slave who planned the uprising. The details of the uprising were reported on a pamphlet, published the following year in London.

- Cuffee was from the Ashanti Kingdom on the African west coast (what is currently inner Ghana). Together with his fellow enslaved Ashanti’s, Cuffee’s plan was to revolt when the sugarcane fields were set on fire at the sound of trumpet shells on June 12th. The slaves would rise up and kill their plantation masters, kidnapping the women, and thus establishing “Cuffee’s Kingdom”. However, this conspiracy was overturned when a female slave overheard the men talking of the revolt and went to her master and reported what she had heard. Her master promptly reported the planned uprising to the colony’s Governor, Jonathan Atkins. The Governor rounded up those who were involved in the plot, executing 17 slaves, six of whom were burned alive, and the remaining eleven beheaded. The bodies were dragged through the streets of Speightstown. The slave who reported the conspiracy to her master was granted freedom as a reward for revealing what Cuffee and his followers had in store for the white plantation owners.-

In 1696 and 1702, small-scale slave rebellions occurred in Barbados. But for more than 100 years after that there are no recordings of such uprisings.

(Present Speightstown: After the leaders of “Cuffee’s Conspiracy” were executed, their bodies were dragged through the streets of the town.)

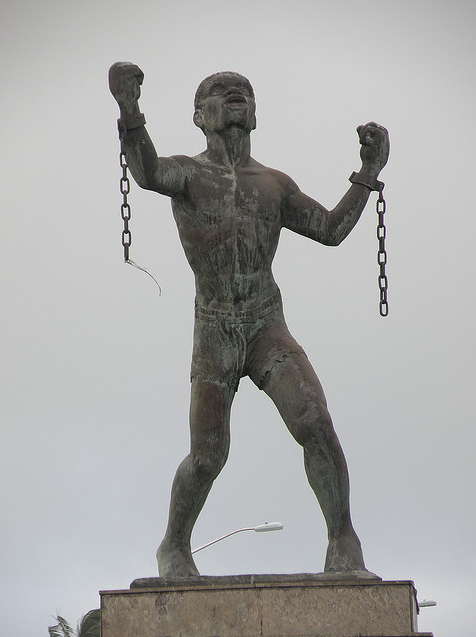

The last and largest rebellion, “Bussa’s Rebellion” to take place occurred in 1816. It still remains in the memory of Barbadians to this day.

Bussa, the slave whom the rebellion centered around, worked on a plantation owned by the Bayley family in St. Philip parish in the southeast of the island. Bussa was a ranger on the plantation- the man in charge of the enslaved workers and taking care of the property. This was a high-level position for a slave; the ability to move around relatively freely allowed him to organize and plan with others before executing the revolt.

His closest partner in the insurrection was a man named Washington Franklyn. He was to ascend the seat of governor if the revolt succeeded, and thus it can be inferred that Bussa and Franklyn had decided upon their respective roles beforehand; Bussa was in charge of military operations while Franklyn was in charge of political matters. Franklyn was of mixed heritage (born to a white father and Black mother) and thus had the status of a free man.

They expanded their circle, creating something like “rebellion caucus”, which in the space of two months furtively held numerous meetings, calling for island-wide support from the enslaved population and asking for obedience to orders from the caucus. The number of men and women who formed the nucleus of the revolt is estimated at around 400, the majority being Creole, descendants of the enslaved Africans.

The rebellion was set for 8pm on April 14th Easter Sunday, a day when the ruling white class would most likely be on low-alert. The flames swallowing the Bayley plantation were the go-ahead signal for the revolt. The violence spread to neighboring parishes in an instant, and the southern half of the island was in a state of chaos. The total slave population on the island at that time was approximately 77,000 people, of which three to four thousand allegedly took part.

Martial law was proclaimed on the entire island after midnight by the authorities with the alarm sounding in Bridgetown by the firing of a cannon. A joint force comprising of 4,000 local militia and British soldiers was formed. Colonel Edward Cobb took command in suppressing the rebellion.

Bussa and his comrades were sure to have taken all necessary precautions for the sake of success of the rebellion. However, when facing the well-trained and well-armed regular forces, they did not stand a chance. Sadly, the rebellion was oppressed in just four days.

A while after the rebellion, an officer gave the following account of events he experienced that night to the Select Committee in the Barbadian House of Assembly established to investigate the insurrection:

“It was about twelve o’clock that we met with a large body of the insurgent slaves in the yard of Lowthers plantation, several of whom were armed with muskets, who displayed the Colours of the St. Philip Battalion which they had stolen, and who, upon seeing the division, cheered, and cried out to us, “come on!” but were quickly dispersed upon being fired on.”

Vast swaths of sugarcane fields were burnt in the insurrection, amounting to a 20% loss of that year’s sugarcane production. 176 slaves including Bussa were killed in fighting. Among captured rebels, 214 including Franklyn were subsequently executed, while only one militia soldier died on the side of the whites.

Although Bussa’s rebellion ended up unsuccessful, the martial law on the island persisted for three months following the incident, proving how much of a shock the rebellion was for white society. On the other hand, Bussa was and remains to this day a legendary figure for the Black population; the revolt he led continues to be passed down from one generation to the next.

Times passed, and eventually in 1966 Barbados gained its independence from the UK, becoming a Black-governed sovereign nation. In 1985, a statue of a standing Black man breaking free of his chains titled “Emancipation Statue” was erected in the area of Haggatt Hall, commonly referred to as the Statue as Bussa by Barbadians. In 1998 the Barbados parliament named Bussa “one of the ten “National Heroes”. Bussa remains a symbol to Barbadians of the resistance to the cruel rule of slavery on the island.

(“Emancipation Statue”-Barbadians refer to the statue as Bussa, the leader of the 1816 Rebellion.)

The Port of Bridgetown, which was previously where enslaved Africans first step foot onto after a months-long voyage across the Atlantic, is now a docking port for luxurious passenger ships cruising around the Caribbean.

“Sunbury Plantation Great House” is located approximately 15 kilometers from Bridgetown. The house was built in the 1660’s by an English man named Matthew Chapman, one of the first colonizers of the island. Incidentally, the site is close to the main battlefield of Bussa’s Rebellion. He built the two-story plantation house for his private family residence; the rest of the property included expansive sugarcane fields and of course a large number of slaves to work the fields.

Sunbury’s ownership changed hands a number of times, being repaired after every hurricane and fire left damages to the building. However, the 300-year-old building is still standing in its original colonial architectural style, and is the only colonial-era plantation house on the island with all rooms available for public viewing.

The exterior walls of the house are 60 cm thick, and the perfectly placed windows let in the trade winds but keep the harsh Caribbean sun out of the room, all aiding to create a comfortable indoor climate. The stately furniture and decor brought from England, the lavish dining room, the surrounding fragrant mahogany forest and sugarcane fields conjure up images of what life as a plantocrat family during the Sugar Revolution might have been like.

The plantation owner’s residence is carefully preserved, but most traces of the slaves’ daily lives have disappeared.

Slaves lived in small wooden shacks called “chattel houses”. Sugarcane depletes the fertility of the soil, thus in order to keep growing the crop it is necessary to frequently designate parts of land to lay fallow for a period. Therefore, slaves were constantly forced to move their living quarters around the plantation. Their houses were moveable wooden structures that could be constructed without nails, built upon a stone foundation. “Chattel” means moveable property, which explains the origin of the name of these moveable shelters. Calling them the precursor to the modern prefab house gives them more credit than they deserve; they were flimsy shacks easily blown away in bad weather, like hurricanes, which may be one of the reasons why there are almost no remnants of the slaves’ living spaces.

However, the Sunbury estate retains only one building which the enslaved used. It is a small church where they offered their prayers to God.

Barbados began conforming slaves to Christianity at the start of the 18th century. It goes without saying that the slaves were not allowed to set foot into the same churches as the whites. The slaves had to pray in segregated churches constructed specifically for them.

The simple, plain building is hardly recognizable as a church except for the cross at the entrance. It is still standing quietly today, set side-by-side the extravagant Sunbury Plantation Great House.

(To be continued in Part 6: Island Fortress of the East Caribbean)

(Exterior of Sunbury Plantation Great House)

(The dining room used for entertaining guests at the Sunbury Plantation Great House. Visitors can get a glimpse into the luxurious lives of the plantation aristocrats of the time.)

(Note 2) In the middle of the 17th century, the infamous pirate-turned-Lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, Henry Morgan, was one of those who lost his livelihood after his indentured servitude was up in Barbados and found a way to Jamaica. (Refer to Section 4: A Genealogy of Pirates)

(Note 3) 30 years after the establishment of the Royal African Company, private companies were allowed to partake in the Slave Trade as well. They were obligated to pay 10% of their profits as taxes; in other words, the government (royal family) was collecting “protection money” from human traffickers.

(Note 4) Countries that sullied their hands in the slave trade were not limited only to England, France, and the Netherlands, but also extended to Sweden, Denmark, and Prussia. These nations also established official government companies involved in the slave trade, and got a small share of what the Great Powers were enjoying.

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.4.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"416th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.3.13 UPDATE

EVENTS

"415th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.2.20 UPDATE

EVENTS

"414th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.1.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"413th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.1.12 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 15"

- 2024.12.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"412th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.12.4 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 14"

- 2024.11.21 UPDATE

EVENTS

"411th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.10.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"410th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"