Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 9)

Section 6 The Fortress Island of the East Caribbean

(A View of the Atlantic Ocean from the East Coast of Barbados)

When I used to live in Barbados, I had some opportunities to sail out to the ocean and realized something. Regardless of the time of the day or seasons, the wind constantly blew to the same direction. This differs from the seas around Japan where the directions of winds frequently change.

“A-ha! This must be the Trade Wind that blows from east to west”; I was fully convinced. I also felt as if I found one of the reasons why Barbados remained under the stable British control for a long period, more than 300 years.

Barbados is in the southeastern part of the Caribbeans, on the small tip of the Lesser Antilles that points out to the furthest east. East to this point, there is nothing but the Atlantic Ocean that extends to the African continent. West to Barbados, there are islands of Antigua, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenada. They all experienced frequent changes in their colonial rulers, as Spain, England, France and Holland fought endlessly for rulership. However, Barbados remained under the British control until its independence in 1966, and never experienced changes in its colonial ruler.

At the time of the British colony, Barbados often faced military threats from the neighboring islands under the control of colonial rivals. Those enemies’ sailing ships travelled eastwards from ports located in the areas west of Barbados. This meant that the troops travelled against the Trade Winds. In order to attack Barbados, they had to frequently repeat tucking of their sails and move zigzag against the head winds. On the other hand, Barbadian ships move smoothly and fast because they were pushed by the tail winds, hence did not allow the enemies’ ships to easily come closer.

One might think “in that case, the enemies could go around the south or north of Barbados, then attack the island from the eastern side, the Atlantic Ocean.” Fortunately for Barbados, however, it was impossible for large ships to approach Barbados from the Atlantic Ocean because its eastern coast facing the Atlantic is rocky and waves are rough. This explains the reason why the English settlers first started to develop the west coast of the island and not the east coast that is closer to their mother land. Even today, there are no major ports on the east coast.

During the Age of Discovery when sailing vessels were used, the location of Barbados was strategically privileged because it was easy to attack other islands from Barbados and to defend itself. This was the reason why Barbados became the undefeatable “Fortress Island of the Eastern Caribbeans”.

Throughout the history of Barbados leading up to today, there was no time when the entire Barbados fell under control of anyone other than England. There were only four occasions when the coast was attacked: ① in 1652, the English fleet led by Admiral Ayscue attacked Barbados because it became too friendly with the Netherlands(see Part III), ② in 1665, the Dutch fleet led by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter attacked Barbados during the second Anglo-Dutch War, ③ during the American Civil War which started in 1775, a privateer ship of the North American colony cannoned Speightstown from the sea, and ④ in 1942, during the World War II, a German submarine U-Boat 514 shot with torpedoes a Canadian cargo ship in anchorage in the Carlisle Bay.

*********************************************************************************************************

Barbados became more and more affluent through cruel slave labor that produced sugar and exports. Once Barbados became the most prosperous English colony in the Caribbeans, non-English people began to visit Barbados and the island started to feature cosmopolitan ambience.

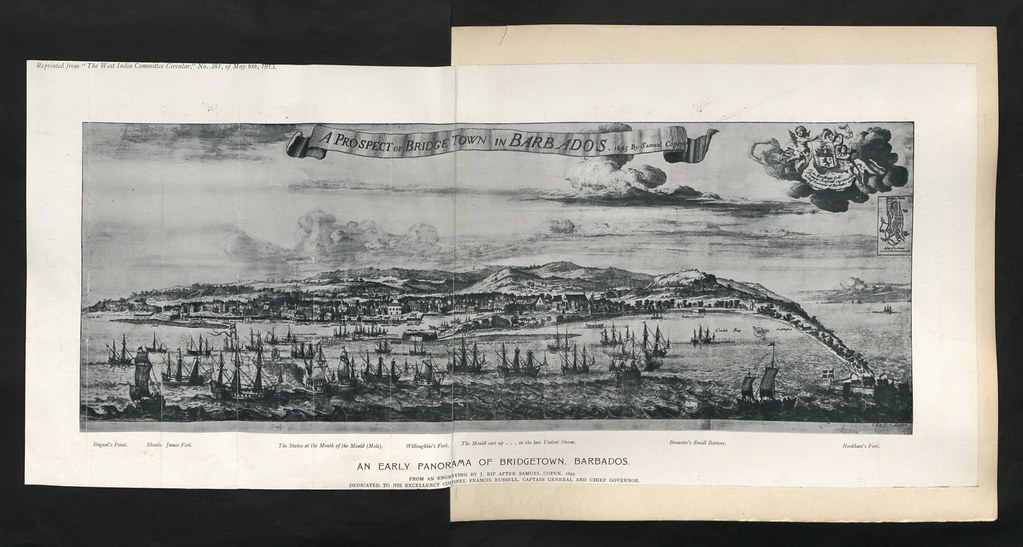

In the etching titled “A Prospect of Bridgetown” by a Dutch man Samuel Copen drawn in 1695, we can see a coastline filled with 3 to 4 story-buildings beyond the Carlisle Bay where numerous commercial vessels were anchored. We can also spot the concentration of fortress with batteries in Needham’s Point on the southern tip of the Carlisle Bay. Those groups of buildings drawn by Copen were burnt by the big fire in 1776, but the streets of the town remain even today as they were back then.

A French Catholic priest, Jean-Baptiste Labat, visited Barbados in 1700 while he was touring various parts of the Caribbeans. He was impressed by the prosperity of the Capital. Labat wrote: “The streets of the Bridgetown are long and clean. The houses are well built and magnificently furnished, the shops and warehouses are filled with goods of every kind from all parts of the world. The planters’ houses are even finer those in the town.”

Before Copen and Labat visited Barbados, a man called Ferdinando Paleologos lived on the island. As some readers may notice, he is a rare figure from the lineage of the last emperor of the Byzantine Empire, Constantine XI Paleologos. The connection between the Byzantine Empire defeated by the Ottoman Empire in the mid-15th century and the 17th century Barbados may appear strange, yet it is a true story.

The pedigree of Paleologos did not die out with the collapse of Byzantine Empire after the fall of Constantinople by the attack of the Ottoman Empire; their descendants spread across Europe. The family of the younger brother of the Constantine XI drifted to Cornwall, England via Italy. Ferdinando Paleologos was born there in 1619.

During the English Civil War, the Royalists were defeated by the Cromwell’s troop at the Battle of Naseby in 1645. As Ferdinando belonged to the Royalists, he fled to the Colonial Barbados. The man from a lineage of the Last Emperor successfully developed a sugarcane plantation on the island. He served the Anglican Church for a long period as the caretaker of the St. John’s Parish Church in the eastern area of Barbados, and eventually became a noted person on the island. Given a nickname, “the Greek Prince from Cornwall”, Ferdinando became a familiar figure and led a peaceful life in Barbados.

Today, in the St. John Parish, there still remains the plantation house “Clifton Hall” where Ferdinando Paleologos used to live, and we can find his gravestone at the cemetery of the St. John’s Parish Church.

(Bridgetown at the end of the 17th century, painted by Samuel Copen)

(The gravestone of Ferdinando Paleologos at the St. John’s Parish Church Cemetery)

Jewish people played certain roles in the development of the Colonial Barbados.

In Part 5 “Sugar, Rum, and Slaves”, I referred to the development of sugar plantations in Barbados owning to the introduction by the Dutch during the first half of the 17th century. In that process, there were many Jewish Dutch who were engaged in teaching techniques for sugar production to the Barbadian farmers and introducing the use of the African slave labor.

How did the Jewish people reach Barbados?

Just around the time when the above-mentioned Byzantian Empire had fallen, there was a significant movement in the opposite or the western end of Europe, the Iberian Peninsula. Around that time, the Christians reconquered those areas (“Reconquista”) that had been under the Muslim control for a long time; this led to the rise of Spain and Portugal. However, in those areas, the intensified persecution of Jews by Christians induced the exodus of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula (they are called “Sephardic Jews”). Some of them strayed and eventually settled in Surinam in South America where religiously lenient Netherlands had a strong influence. Some also settled around Recife in Dutch Brazil. By the end of 1630, Jews constituted a significant portion of around 10,000 residents in Recife.

Some of those Jews managed the sugarcane plantations in South America. They used Dutch Curacao Island off Venezuela as the base to trade African slaves, and started to spread the sugar production technology and the use of slave labor to other Caribbean islands.

However, once Portugal began to counterattack in the Northeastern Brazil where the Dutch influence was once prominent, the Jews started to leave (Dutch Brazil collapsed in 1654). In addition, anxious Jews started to leave from Surinam and French Guyana centering around Cayenne. It seems that there was a stronger tendency for the Catholic Portugal and Spain to persecute the Jews, rather than the Protestants.

Many of those Jewish people returned to the Netherlands and other parts of Europe, but a part of them found opportunities in Barbados, Jamaica and some other islands of the Caribbeans.

However, in Barbados where the land area is limited, there remained little space to accommodate the development of new plantations. As such, the Jews managed shops or were engaged in foreign trade. In Bridgetown and Speightstown, they formed Jewish quarters. In Bridgetown, there was a period when the Jews constituted more than 10 percent of the total households. The street in the town center, where many shops operated by Jews were concentrated, came to be called the Jewish Street and they also built the Jewish Synagogue (Nidhe Israel Synagogue).

In 1661, the Jewish merchant union secured a permit of the islands’ Colonial authorities to directly trade with Surinam, and this enhanced their economic power. For many Jews, Surinam was their settlement in the past. Their network and the local knowledge gave them an advantage in conducting business and trades.

Yet, some people in Barbados were annoyed to see the Jewish people becoming wealthier. They were the mainstream English settlers. In 1668, the Jews were prohibited by law from trading and buying slaves; they were also obliged to live within the ghetto in Bridgetown.

Despite the emergence of discriminations in Barbados, the Jewish population steadily increased through the 18th century. This probably was made possible by the availability of sufficient opportunities for the commercially talented Jewish people to survive, given the profitable sugar industry that allowed the affluence of the economy (note 3).

As the vibrant sugar industry in the Caribbean islands came to be known in Europe as the golden goose, territorial battles between countries intensified. The colonial Barbados naturally started to build its self-defense.

Ever since the English colonization started, Barbados had an armed body called the “Militia” who kept the island in order and protected the island from the external enemies. Initially, the militia consisted of soldiers who volunteered to serve. Starting in 1652, landowners above a certain level were obliged to contribute a family member and a horse. Each unit of the militia was commanded by a professional who had an experience in serving the English military. When an enemy’s ship approached the island, hundreds to thousands of militia soldiers were mobilized.

The first time when the official English Navy vessel came to Barbados was in 1651 when the fleet led by Admiral Ayscue attacked Barbados. The next was in 1655, when the fleet led by Admiral William Penn came, and this visit was a friendly one from the colonial metropole. The Penn fleet was comprised of 16 vessels, and they stopped in Barbados on their way to take over the Spanish territories, Islands of Jamaica and Hispaniola (currently Haiti and Dominican Republic).

After recruiting additional soldiers from Barbados, the fleet went north. While they failed to take over Hispaniola, they succeeded in practically occupying Jamaica. Thereafter, Jamaica was handed over to England from Spain through the Treaty of Madrid in 1670 and formally became the English territory.

As such, Barbados colony was increasingly used as the base for advancement for the English naval fleets, to defend its territories in the West Indies and to supply soldiers and goods into the fleets that attacked the islands in the hands of other rival countries. This island became the Bridgehead Fortress for the England’s advancement in the Caribbean, supplying its fleets with food and commodities, and providing slave workers, hence bringing massive profits.

Rivalry with the Netherlands

Throughout history, superpowers in the international arena have used every reason and means to defeat anyone who challenge them. This led to mutual sanctioning and sometimes to wars. Then, small countries got caught up.

It was during the Anglo-Dutch Wars when Barbados was first exposed to a military threat from a foreign state other than the suzerain.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars occurred three times during the latter half of the 17th century (1652-54、65-67、72-74), and their naval forces battled in the Strait of Dover, the North Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean. The War was triggered by the Navigation Acts enacted by England, intending to hinder the Dutch marine commercial interest.

The Netherlands had rapidly developed its maritime trade and expanded its engagements not only in Europe and the new continents but also in Asia. This annoyed England who was still in the process of establishing its maritime hegemony. As the Netherlands deepened its presence into the English markets in various parts of the world, the anti-Dutch sentiments arose among the proud people in England. At that time, England was temporarily a republic known as “the Commonwealth of England”, ruled by Oliver Cromwell who led the English Civil War.

England, for quite some time, had mobilized the Royal Navy as well as privateers holding the Royal permit, and expanded its maritime hegemony by intruding into the areas previously controlled by old powers such as Portugal and Spain. As such, England expanded its economic sphere based on a notion “what’s wrong for the fittest to make profits?” or a logic of quasi “free trade principle”. However, when England was confronted by the emerging Netherlands, it adopted in 1651 the Navigation Act that was targeted to the Netherlands. In other words, England who had developed by trading freely, flipped its policy and excluded the Dutch ships from trade activities within the English colonies. The protectionist measure was equivalent to today’s so called “unilaterally imposed sanction”.

The Netherlands, who made profits by taking advantage of the domestic confusions in England during the Civil War, challenged England and demanded “free trading”. Thereafter, English navy vessels and privateers continued to capture Dutch ships, while angry Dutch responded with provocative behaviors. In 1652, a coincidental collision in the Dover Straits triggered the firing of gun of the first Anglo-Dutch War.

During a series of naval warfare, England and Dutch each won some and lost other battles. Notwithstanding, England remained in advantage and the Dutch recognized the English Navigation Act leading to the ceasefire of the first Anglo-Dutch war.

After settling into peace with the Netherlands, Cromwell immediately intensified attacks on the old enemy in the Caribbeans, Spain. As stated earlier, Admiral Penn took Jamaica from Spain by force (note 4).

<Invasion of the Dutch Fleet>

It was during the second Anglo-Dutch War, when Barbados was caught in the conflict.

England returned to Monarchy after the passing of Cromwell. However, conflicts with the Netherlands remained. The England’s interference in New Amsterdam (presently New York), the Dutch colony in North America, inflicted the second Anglo-Dutch war. This time, England had trouble in the battles because France, another competitor, allied with the Netherlands.

It was the fleet that attacked Barbados, which was led by Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, distinguished in numerous sea battles. When the second Anglo-Dutch war started, de Ruyter’s fleet was cruising in the Mediterranean Sea, but Johan de Witt (note 5), a political leader of Holland, ordered the fleet to go to the Caribbeans. This operation was to devastate the English colonies and disturb England from behind. De Ruyter’s fleet, comprised of 12 ships, attacked at the offset the England’s fortresses in the West Africa and then headed for the Caribbeans.

On April 29th, 1665, de Ruyter reached offshore of Barbados, and shot cannons on the eastern area from the Atlantic. His intent was to land on Barbados, but he realized the eastern coast was unreachable as it was filled with rocky reefs. The next morning, he detoured the course and steered the ship to the South, towards the Carlisle Bay.

However, the Militia forces protecting Barbados, had anticipated this and prepared for the enemy’s arrival in their fortress. When de Ruyter’s fleet rushed into the Carlisle Bay, approximately 20 commercial vessels in the Bay and land-based batteries all started shooting. Those anchored ships appeared as commercial ships, were fully armed vessels carrying cannons.

The fleet’s flagship “Spiegel” (“Mirror” in English) in which de Ruyter was on board, was badly damaged by the cannon shot from the Needham’s Point. As several other ships were also damaged, the fleet had no choice but to retreat. The Militia soldiers defending Barbados shouted at the retreating Dutch fleet “Don’t’ ever return!”. De Ruyter never returned to Barbados.

(Dutch Navy Admiral Michiel de Ruyter)

Years later, the Dutch Navy named some of its battleships, “de Ruyter” (Note 7). A portrait of Admiral Michiel de Ruyter was shown on the 100 Guilder (NLG) bill, before the Netherlands adopted the European currency, Euro. They indicate that the Navy Admiral, de Ruyter, marked the history of the Neverlands.

Perhaps, Barbados deserves a praise for having pushed back the attack led by the renounced Dutch Commander, even after taking into consideration that de Ruyter fleet would have been consumed by the long cruise across the Atlantic.

It is the author’s view that, Barbados was not attacked by foreign enemies for long period of time thereafter because it had prevented the invasion by defeated de Riyter’s fleets. This gave lessons to other nations that touching Barbados would be something like playing with fire.

The Anglo-Dutch wars, that involved three phases, was finally concluded in 1674. The outcome of this conflict has usually been explained as “the England’s victory”. However, England never succeeded in invading into the Neverlands. From a military perspective, it was a lukewarm end of the war because of the exhaustion of both parties. However, the prolonged wars had adversely affected the military and economic strength of the Netherlands. It is safe to conclude that, on one hand England led the struggles for supremacy and became the superpower; on the other hand, the Netherlands fell into the middle power route (note 8).

To be continued in part 6 "The Fortress in the Eastern Caribbeans"

(Note 2) “Jewish Street” is now called “Swan Street”, and is a popular shopping street in the central part of Bridgetown.

(“Swan Street” in Bridgetown. In the 17th century it was full of shops run by Jewish people and was called “the Jewish Street”.)

Presently, there is a small Jewish community in Barbados. They are Ashkenazi Jews from Europe who immigrated during the World War II, escaping from the persecution by Nazi. The Nide Israel Synagogue, that was abandoned for a long period of time since the departure of the Sephardic people, finally started its operations by Ashkenazi people in 2008.

(Note 4) Despite his accomplishment in the Caribbean, Admiral Penn was imprisoned by Cromwell upon his return to England. He was discharged after a brief period, but temporarily migrated to Ireland. After the restoration of Monarchy in 1660, Admiral Penn was able to return to England.

As a side note, Admiral Penn’s son, William Penn, later became the Governor of the Pennsylvania colony in North America and built Philadelphia City.

(Note 5) Johan de Witt was de facto the highest political leader of the Dutch Republic during the Stadtholderless Period. Later, his failures in the internal and external governance led the people to massacre him together with his older brother, Cornelis de Witt, in the Hague in 1672.

(Note 6) France sided with the Netherlands during the Second Anglo-Dutch war, but sided with England during the Third Anglo-Dutch war under the “Secret Treaty of Dover”, and conspired to invade the Netherlands.

(Note 7) The battle-cruiser “De Ruyter” of the Dutch Navy launched in 1936, fought deadly battles against the Japanese Imperial Navy in the Southeast Asian Sea. In the end, it was sunk offshore of Surabaya in 1942 by torpedoes of the Japanese cruiser “Haguro”.

(Note 8) Ironically, after the Anglo-Dutch Wars and as a result of the Glorious Revolution in 1688, England accepted the Dutch ruler (stadtholder) Willem III, as the English King William III.

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2024.12.4 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 14"

- 2024.9.17 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 13"

- 2024.7.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"408th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.7.23 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 12"

- 2024.7.9 UPDATE

ABOUT

"GREETINGS FROM THE PRESIDENT JULY 2024"

- 2024.7.4 UPDATE

EVENTS

"APIC Supports 2024 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2024.6.27 UPDATE

EVENTS

"407th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.5.21 UPDATE

EVENTS

"406th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.5.14 UPDATE

EVENTS

"405th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.4.2 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Water Tanks Donated to Island of Wonei, Chuuk, FSM"