Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 12)

Section 7 The Path to Abolishing Slavery (Cont'd)

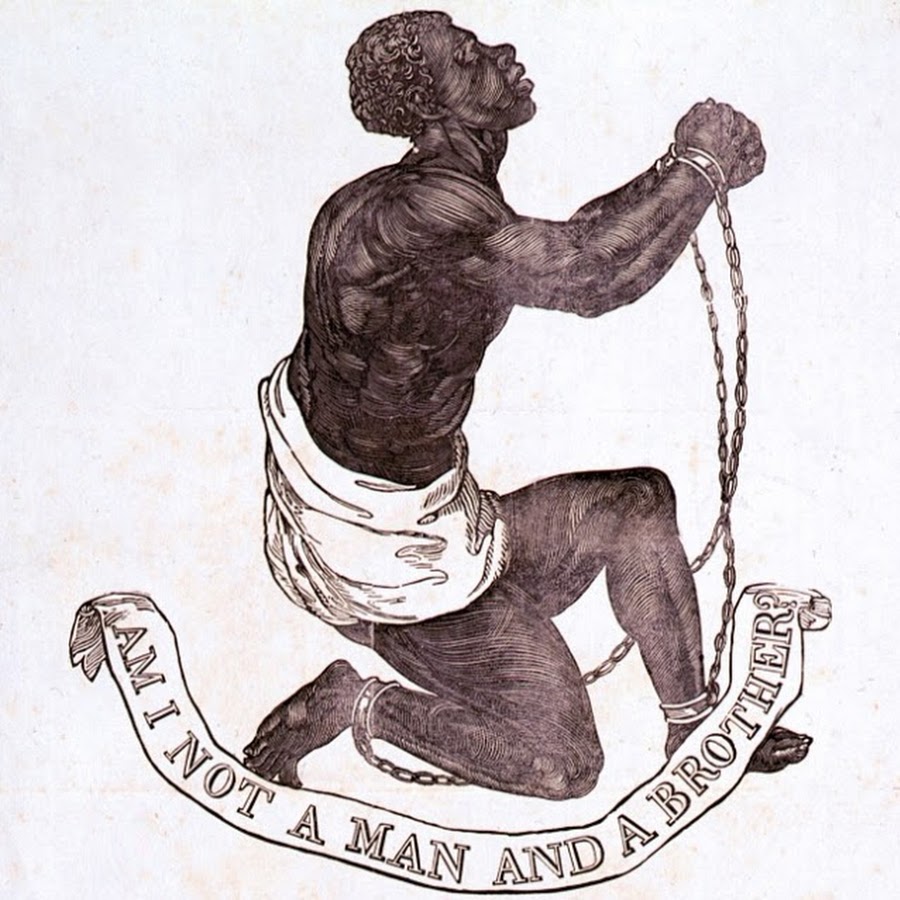

(The design used for the symbol medallion of the abolitionist movement, created by the founder of British porcelain maker Wedgwood, Josiah Wedgwood, in 1787)

Another Face of the Slave Trade Act

In this section I would like to take a look at an external factor concerning the process of the creation of the Slave Trade Act in Britain.

The factor is the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon-affairs of great consequences for continental Europe.

The upheaval occurring on mainland Europe overwhelmed Britain, and discussions regarding the Slave Trade Act came to a halt as the time was deemed inconvenient.

Rioters’ storming of the Bastille ignited the French Revolution in 1789. Napoleon appeared out of the haze and confusion of the revolution and was crowned Emperor in 1804, which was around the same time when William Wilberforce was giving all his energy into fighting for his anti-slave-trade bill in the British Parliament.

In the previous post I talked about how Napoleon tried to use the Berlin Decree to cripple Britain’s economy after his defeat the prior year in 1805 at the Battle of Trafalgar against the British navy. Interestingly, Wilberforce’s anti-slave-trade bill finally saw the light of day in parliament soon after in 1807.

The Slave Trade Act included an extraterritorial jurisdiction clause (in layman’s terms, the law applies both inside and outside of the issuing country), which is occasionally seen in laws of countries of Anglo-Saxon origin. The British government was going to clamp down not only on its own ships transporting slaves across the ocean, but it was also supposed to inspect and capture foreign ships carrying slaves.

The idea for such a clause can only be conceived by a maritime power who considers the whole Atlantic Ocean their playing field. It was this clause that allowed British fleets to attack French ships on the premise that France was still active in the slave trade and that the enemy’s ships were “carrying or might be carrying” slaves (note 1).

There is no doubt that Wilberforce’s determination and genuine passion to pass his anti-slave-trade bill on the grounds of humanity was what guided the bill to success. However, the final result after passing through the House was the Act that played a role in countering the damage done by Napoleon’s Berlin Decree. One could say that the Act had hidden purpose under a seemingly good-intentioned law.

In fact, Britain had a slave trade surveillance post in its west African colony of Sierra Leone, from where they enforced the Act not only to British ships, but to French ships and ships from countries such as Spain, the Netherlands, and others under the French empire. It is said that thousands of British soldiers died or were injured in the battles. In reality a war was being carried out under the pretense of the noble cause of stopping the slave trade.

The Abolishment of Slavery

In 1815, Napoleon fell from power and was banished to the island St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. The British abolitionist movement subsequently took up speed after the end of the Napoleonic wars and the re-organization of continental Europe at the Congress of Vienna.

In regards to the emancipation of slaves, Wilberforce, the father of the Slave Trade Act, seems to have had the following view:

“If the slave trade is banned, then it will become necessary to preserve slaves and their offsprings in the plantations of British colonies, thus the treatment of slaves will eventually improve. Certain social conditions are necessary for emancipating the enslaved, thus the system should not be abolished all at once, but instead should be broken down in steps.”

However, in reality it is largely acknowledged that the treatment of slaves in Barbados and the West Indies did not improve much after the Slave Trade Act was enacted. This is thought to be due to the cutting off of the supply of young, healthy slave labor from Africa (note 2), which consequently caused the worsening of labor conditions on the island while a relative ageing of the slave population progressed.

The conditions surrounding the enslaved workers were as cruel as ever, and large-scale uprisings in the slave communities occurred throughout all of the British colonies in the Caribbean.

The first rebellion to occur was in Barbados, the previously-mentioned Bussa’s Rebellion in 1816. Following this was a revolt in 1823 in Demerara (currently a region in Guyana), and in 1831 a revolt of an unprecedented scale took place on Christmas day in Jamaica.

In 1804, preceding the British Slave Trade Act, the French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) became the world’s first Black independent nation, Republic of Haiti, as the result of a slave rebellion. This was a flame of hope for the future of the slaves in the British Caribbean colonies (note 3).

The revolts in Barbados, Demerara, and Jamaica were eventually suppressed by the colonial militia and British army. Looking at the situation from the point of view of the plantation owners, Haiti’s independence set a nightmarish precedent. The suzerain Britain’s Slave Trade Act was, in the eyes of the plantation owners, an unjust law, giving the enslaved the improbable expectation that they would be freed momentarily. Resentment from the colonies towards Britain’s abolition movement was always stronger than the motherland, as the crux of their lifestyle and economy relied heavily on slave labor.

On the other hand, forces behind the anti-slavery movement in Britain began to pick up speed, making the movement irreversible. There’s no doubt the movement was based on humanitarian standpoints, but it is also undeniable that the mood in Britain towards slavery started changing when they saw slave revolts in the colonies started becoming a serious challenge.

At the end of the 18th century, a boycott of sugar produced in the West Indies took place in Britain. The boycott urged consumers to buy sugar made from “free labor” in Asia as opposed to sugar from the West Indies which was made by inhumane slave labor.

Recently, some developed countries in the West have boycotted the import of products made in a specific area of a certain country near Japan based on their “inhumane” production. The origin of these boycotts may just lie in past English boycotts against items made under working conditions the West considers unjust.

In 1821, a Quaker named James Cropper set up the Liverpool Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery in Liverpool, one of the slave trade centers. Similar groups were established in various parts of Britain afterward, with the abolitionist heavyweight Wilberforce and other members of parliament joining the London Society.

In the 1830 British Parliament elections, the Whigs (later the Liberal Party) won against the Tories (later the Conservative Party), their base supporters being large landowners. The change in power after seventy years also helped the abolition movement gain even more traction.

The abolition movement phased into a mass movement, and nationwide abolition societies propelled the speed of the abolition process from gradual to immediate.

On August 23rd, 1833, while the shock of a series of the Caribbean slave uprisings was still lingering, the British Parliament passed the Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies, abolishing slavery in Britain and all of its colonies. This act was approved 26 years after the Slave Trade Act, and one month after the death of lifetime abolitionist William Wilberforce at 73 years of age.

The law went into effect one year later on August 1st, 1834, and is a national holiday celebrated today in Barbados as Emancipation Day.

A New Social Class

I have given a brief history of the abolition movement in Britain, and the events leading up to the abolition the slave trade and of slavery itself. Let’s turn our attention back to the colony of Barbados to see what was going on there at this point in history.

As we have seen, the bipolar system of the Plantocrats cruelly suppressing the much larger African slave population continued for a long time. However, during the 18th and 19th centuries, a new class emerged from between these two groups.

One of these was the class of small freeholders who cultivated their own land (the Yeomanry). This social group of whites, also called “10-acre men”, did not belong to that of the white plantation owners, and steadily farmed their small plots of land. Being white, they were able to receive an education at schools, and were literate. This social class would later on begin to encroach upon the Plantocrats’ control of the island.

At this time Barbados was facing a series of difficulties. An infestation of pests and field mice dealt a big blow to the sugarcane crops; the prices of imported necessities such as flour, corn, and lumber from North America skyrocketed because of the Revolutionary War. In 1780 a powerful hurricane delivered catastrophic damage to the island; to top it all off was a smallpox and yellow fever epidemic enveloping the island.

Following all of this was Britain’s Slave Trade Act and Bussa’s Rebellion. The rising of the abolition movement in the mother country and the slave rebellion in Barbados, which nearly caused a “second Haiti”, shook the trust of the Plantocrats’ ruling system of the colony, which up until that point had been unquestioned.

During all of this, the economic and political voices of the Yeomanry began to be heard. In 1818, a Yeoman named Michael Ryan started publication of the newspaper “Barbados Globe” as its editor. Ryan’s newspaper was to take a stance against the Plantocracy-leaning conservative paper “Western Intelligence”.

The conservatives fought back against the Globe and the newly-emerging Yeomanry using the Western Intelligence and the Parliament. Ryan was accused of “slandering the influential men on the island, creating a disturbance”. However, the court found him innocent amid protests and meetings held in support of Ryan, causing the conservative class to lose face.

As a result of the Barbados Colonial House of Assembly’s election in 1819, candidates with the Yeomanry as their support base won more than half of the seats for the first time.

The Governor and Upper House still held the majority of the power, as they represented the wealth of the Plantocracy, and thus the House of Assembly’s strength should not be overrated. Yet, it can be said that the results of this election are what created Barbados’ middle class.

The Role of Free Colored People

Incidentally, how did the Black slaves gain knowledge about events such as the independence of Haiti or the abolition movement in Britain?

Needless to say, as slaves were deprived of a formal education, they were unable to read any type of printed document, such as newspapers and official decrees. Much less did the white slave owners tell the slaves any information that would cause trouble for themselves. With limited freedom, the number of opportunities for the slaves to learn about current news and affairs from outside the island should have been very limited.

In reality, the enslaved population had information sources which kept them informed of the goings on of the outside world.

It was in the middle of 17th century that slaves from the African continent began to be systematically “imported” to Barbados. Accompanying the increase of the enslaved population was the inevitability of offspring being conceived between the two races. This is not peculiar to Barbados-this was a common phenomenon in other colonies as well. Almost without exception, these mixed children were born to white fathers (“masters”) and Black mothers who were slaves on their plantation.

There were many cases where mixed children were not recognized by their father and became slaves, or disappeared into the dark without a trace. However, among these mixed children were ones who were recognized by their fathers and became standing members of the free white society as “free colored people” (note 4). Having a father with a certain level of social status and wealth, they were able to move around as a free person.

The majority of free people of color and were mixed-race people called “Mulattos”. I will go into more detail later, however, after the end of slavery in Barbados, not only Blacks but Mulattos also played an important role in elevating the status of non-whites and modernizing the island.

Among the population of free people of color, there was a small number of Black former slaves vis-à-vis Mulattos. Reasons why they were free might vary, such as being especially capable and/or having made a big contribution to the success of the plantation, among others. There were exceptional cases where Blacks who won the favor of Masters became free people emancipated from the status of slave (note 5).

The number of free colored people in Barbados in the 17th century was very low, but in the 18th century the number gradually increased, and in the 19th century the number saw a sharp increase. According to the 1802 population survey, there were 2,168 free people of color on the island; in 1829 the number had increased more than two-fold to 5,146, and with the abolition of slavery in 1834 the number was close to 7,000 people, approximately 6% of the total population.

Among this free colored population, there were people who had received a formal education and were able to understand information in written form. They were able to hear and read the news directly from within white society. At the same time, there were those who felt righteous indignation against the situation of the enslaved as they, due to their birth origin, had close contact with the slaves in daily life.

The people who relayed information to the enslaved regarding the ongoings inside and outside of the island were a select number of these free colored people. Unobserved by the plantation owner, the enslaved would sit in a circle at the feet of the free colored person who came to read them the newspaper, earnestly listening to news about uprisings on other colonies or the progress being made in the British parliament. This was how new information was spread among the slaves.

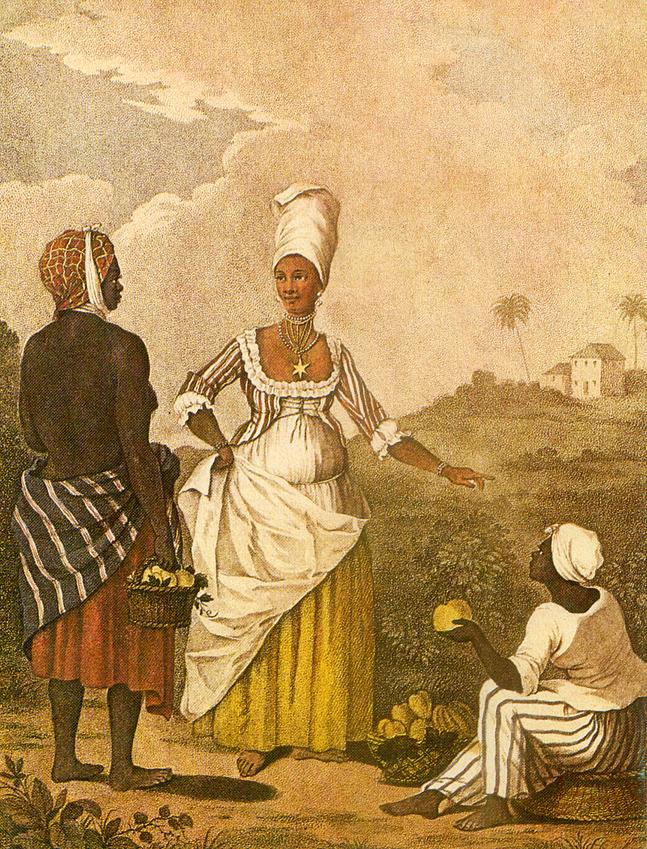

(Painting titled "The Barbados Mulatto Girl" from around 1770)

I mentioned previously that the man who worked with Bussa, leader of the 1816 Rebellion, was a free Mulatto man named Franklin Washington.

It is thought that Franklin was born around 1782, and his father, of all people, was the plantation owner of Bayley’s plantation-the stage of Bussa’s Rebellion-Joseph Bayley. His mother was Leah, a Mulatto slave who worked under Bayley. Joseph Bayley died after giving his son Franklin the status of a free man, as well as leaving him a hefty sum of money.

However, Franklin’s testimony at court to receive his father’s inheritance was not recognized on grounds of him being Mulatto, and thus he was unable to inherit the money his father left for him (note 6). This angered Franklin, causing him to take action and revolt against the system. Soon afterward, he got into a fight with a white man, and was thrown into jail for six months on the charge of threatening to beat him up.

The friendship between the free Franklin and Bussa, who was a slave ranger at Bayley’s plantation started around this time, when the plantation had been passed over to the hands of a white relative after Joseph Bayley’s death.

It was probably Franklin who knew of the goings-on of the world, such as the slave revolt that led to the independence of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), the establishing of the Slave Trade Act, and thus inspired Bussa and the slaves to fight back.

The white society of the time assumed that it was nearly impossible for only Black slaves to organize and proceed with a large-scale rebellion the size of Bussa’s Rebellion, so someone from the outside must have assisted them in their planning. In the book “The History of Barbados” by Robert Schomburgk in 1848, he writes of the Rebellion as such: “There is no mistaking that Franklin Washington was the one who contrived the revolt, plotting the rebellion that brought so much devastation to the island.”

In addition to Franklin, two free Mulatto men, John Richard Sarjeant and Cain Davis, were also at the center of the rebellion. Bussa was killed while fighting on the frontlines of the rebellion, but the three free Mulattos were captured and taken to the authorities. In the report put together by the Select Committee of the Barbadian House of Assembly in order to wrap up the aftermath of the rebellion, John Richard is quoted as saying “You all have to fight just like your comrades in Saint-Domingue”, rallying up the slaves at the start of the revolt. Cain, on the other hand, was quoted as saying “slaves must be freed. I read in the newspaper that Wilberforce said so… It was me who lit fire to the corn stalks.”

After the suppression of the rebellion, the three Mulatto men were executed along with more than 200 Black slaves.

Rachael, a Female Entrepreneur

While there were free people of color who lived tragic lives such as Franklin Washington, there were also those who were successful in business in an obscure corner of the upper echelons of white society, as well as those who were able to acquire ownership of plantations.

Social status and rules and regulations regarding free colored people differed colony to colony. For example, there were strict rules in place in Jamaica regarding occupation and land acquisition for free Blacks and Mulattos. In contrast, Barbados was comparatively generous in this respect and did not have that many restrictions. It is for these reasons that some free people of color were able to make good use of their resources and artfully make a name for themselves in the free world.

There was a woman who Barbadians remember to this day fondly by the name of Rachael Pringle Polgreen (1753-1791).

Not only people from within the island, but also people such as merchants and sailors from across the seas gathered in Barbados’ capital of Bridgetown. There were many free women of color who ran dining establishments and inns in the capital. The Royal Naval Hotel ran by Rachael was one of the most successful inns of all of them.

Rachael was born to a father of Scottish origin and a Black enslaved mother. At the age of 16 she was bought by a British naval officer named Thomas Pringle who made her his lover in return for paying for her freedom. Then, with the house she was given by him in Bridgetown she started her own inn.

Thomas left Rachael after a while and ran away to Jamaica. However, Rachael gathered a number of good-looking enslaved women and hired them to work in her “inn of beautiful women”, hitting the business jackpot.

There is an anecdote about this Royal Naval Hotel.

Just as the name suggests, the inn catered to British naval officers and sailors who anchored in Barbados. There was a young naval officer who sometimes stopped in.

One night, in a drunken stupor he became violent and destroyed the inn; the next morning Rachael served him a bill with the repair costs. He meekly apologized and compensated more than the amount on the bill, allowing Rachael to make major improvements and have a better-looking interior than before.

This might sound like a common story, but this unbelievable naval officer’s name was none other than Prince William Henry. He was in the Caribbean as part of Nelson’s fleet, and 30 years after causing trouble at Rachael’s inn, this man would go on to become King of the United Kingdom, William IV, fondly called the Sailor King. (On a side note, William IV was the uncle of the late Queen Elizabeth II’s great-grandmother, Queen Victoria).

Rachael’s inn earned even more profits after this incident, buying up the surrounding buildings and land to increase her wealth. She became well-known as “the woman entrepreneur” throughout the island. But as you may have easily imagined, her inn and others like it also served as a brothel in addition to a traditional resting place.

If the Prince had shown such misconduct in today’s world, he would have immediately become the target of the media, blowing up everyone’s social media feeds with his debauchery. However, even this incident of remote antiquity is etched into history, so shall we always say that for public figures, “actions speak louder than words”.

In any event, depending on perspective, it is not impossible to say that Rachael was the “big sister” of the red-light district. However, just like in Japan and other parts of the world, earning money in this industry was not necessarily illegal in the past.

In a direct quote from a book of that time, it states:

“[In the West Indies] One privilege, indeed, is allowed them, which, you will be shocked to know, is that of tenderly disposing of their persons; and this offers the only hope they have of procuring a sum of money, wherewith to purchase their freedom: and the resource among them is so common, that neither shame nor disgrace attaches to it; but, on the contrary, she who is most sought, becomes an object of envy, and is proud of the distinction showed her.” (Note 7)

Rachael, who lived strong, died at the young age of 38 from disease. She penned a will two days before her death, leaving behind enough money for six of the 19 girls she hired to buy their freedom, and for the remaining 13 enslaved girls to live under them.

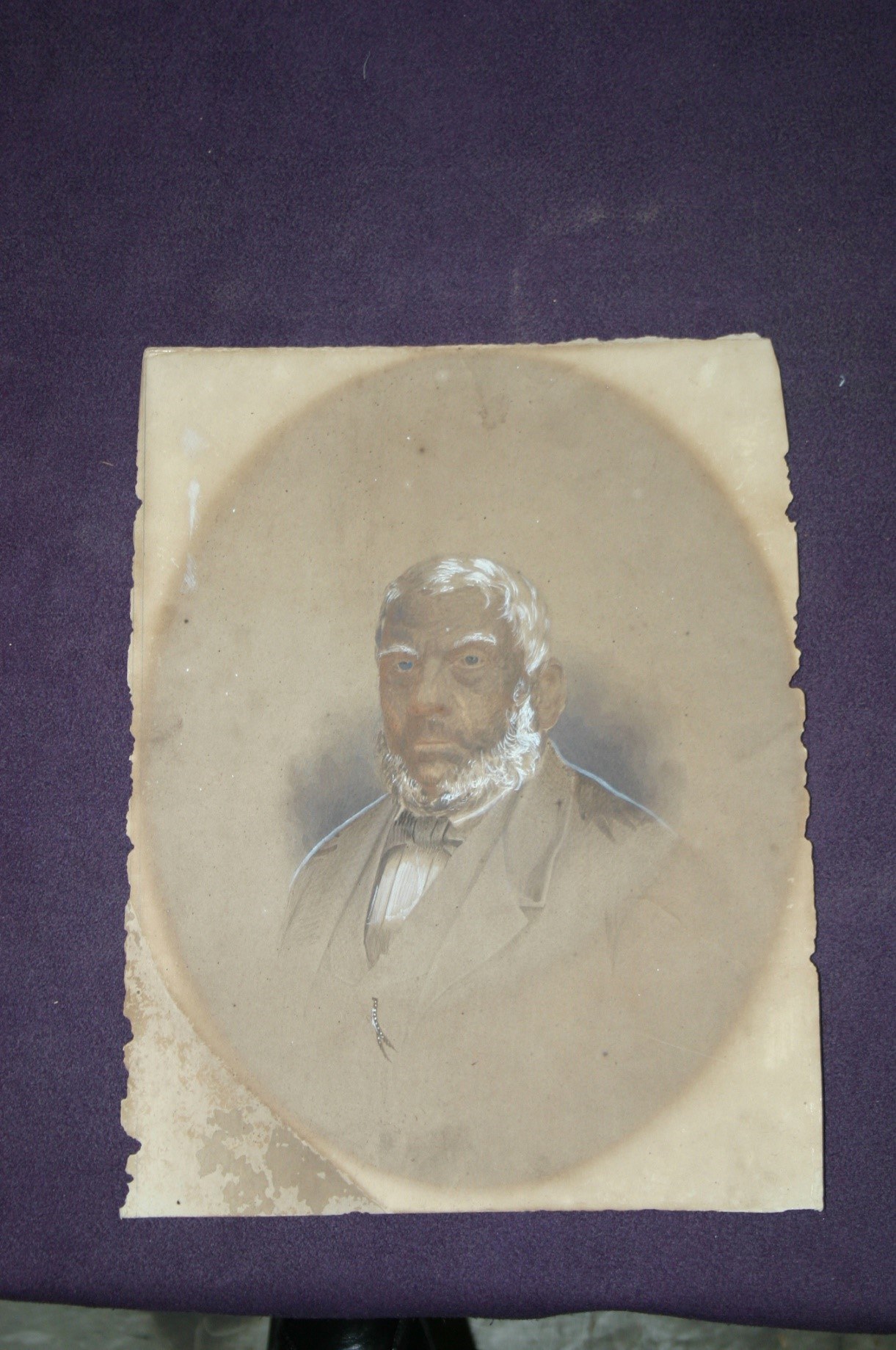

(Rachael Pringle Polgreen)

Here is another example of success achieved by a free Black person.

There was a free Black man named London Bourne who lived from 1793 to 1869.

Bourne’s father William was born a slave, but his exceptional skill as an artisan allowed him to save up enough money to buy his own freedom. When London was born, his father was already a free man, but his son was born a slave. Thus, it can be assumed that a child born to a free Black citizen was not automatically free at birth. Using his profits from his successful business endeavors, William bought his family’s freedom, his wife, London and other children- when London was in his mid-20s.

Following in the footsteps of his father, London found success in the sugar brokerage business. Alongside maintaining a number of stores in Bridgetown, he also lent money to borrowers, no matter their skin color. He married a free Black woman named Patience and together they had seven children.

Not only was he a sharp merchant, he was a highly respected person of character and intelligence. But despite these assets setting him a cut above the rest, his skin color was the source of many frustrating experiences.

When Bourne tried to become a member of the merchants’ club where the wealthiest merchants on the island gathered, he was denied on the basis of his skin color. The irony of the situation was that Bourne was renting the premises to the club. One can easily imagine that the injustice of not being allowed to set foot into his own building was unfortunately the norm at the time.

Never being defeated, Bourne expanded his business, buying a plantation, and eventually opening a mercantile agency in London. He even hired white clerks to work at enterprise, which was a very rare occurrence at the time.

Slavery in Britain and Barbados was outlawed while Bourne was alive. In his later years, the successful Bourne was a prominent financial backer of movements to improve education among the poor Black population and the improvement of social positions of non-whites.

He also has some well-known descendants.

Before the abolition of slavery in the United States, many free Blacks decided to “return to the homeland”. They headed towards Liberia, a country on the west African coast founded in 1847.

There were also Blacks from Barbados who went to Liberia in hopes of starting a new life. London Bourne’s daughter Sarah and her husband and their child Arthur Barclay were among those who immigrated to Liberia in 1865.

Arthur, who was Bourne’s grandchild, would later become the 15th President of Liberia from 1904 to 1912. In addition, Bourne’s great-grandson Edwin James Barclay served as Liberia’s 18th President from 1930 to 1944.

Returning to present times, in 1997 the building that used to house the merchants’ club that Bourne was denied entry to was torn down due to deterioration. The Barbados government used the site to build housing for low-income families, naming the building “London Bourne Towers”.

(Photo of London Bourne. Taken from Barbados Museum & Historical Society official Facebook page.)

(Note 1) France actually abolished slavery one time before Britain did. After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1791, a slave revolution led by Toussaint Louverture occurred in the colony of Saint-Domingue (later Haiti). The rebels demanded an end to slavery, and the First French Republic, led by Jacobist Maximilien Robespierre, made the decision to end slavery in 1794. However, Napoleon, who later held power by a coup d’état, brought back slavery in 1802. (Hence, when England introduced the Slave Trade Act in 1807 France was involved in the slave trade.) There is a theory that the reason Napoleon brought back slavery was because his wife Josephine was from a ruined aristocratic family in the colony of Martinique, not too far from Barbados. When news of the reinstatement of slavery reached Haiti, the Haiti Revolution broke out, and in 1804 it achieved independence. After the fall of Napoleon, France banned the slave trade in 1820, and in 1848 under the Second French Republic slavery was abolished.

(Note 2) In the 1807 Slave Trade Act, the fine for breaking the law was merely 100 pounds per slave. This minimal fine was one of the contributing factors to the continuation of the smuggling of African slaves into the colonies. Although long-term imprisonment and exile to Australia were added to the list of punishments for breaking the law in later reforms, it is thought that smuggling continued to persist in a number of forms until the late 19th century.

(Note 3) In 1825 France demanded Haiti pay reparations in exchange for its independence, which Haiti paid. In 1947, 122 years after its independence, Haiti paid off the loan, interest, and fees totaling approximately 28 billion USD in today’s value. In April 2003, then-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide demanded France repay Haiti’s reparations. When then-President of France Francois Hollande visited Haiti in May 2015, he brought joy to Haitians when he claimed that “France will repay its debts to Haiti”, but on his next stop to Guadalupe, a French overseas department, he clarified his poorly prepared remarks, saying “’debts’ refers not to legal and monetary debts, but to the ‘moral’ debt” owed to Haiti.

(Note 4) The term “free colored people” was used to categorize non-whites who were not enslaved, and who were able to live without many restrictions that those who were enslaved lived under.

(Note 5) In Barbados, there were regulations regarding the freeing of slaves “owned” by whites. However, in 1739, an obligation was put into place requiring slave owners to pay a sum of money to the local authorities when freeing slaves. This was due to the increasing number of slaves who were left outside plantations in order to reduce costs when they could no longer work as a result of sickness or age.

(Note 6) In the beginning, Barbados allowed free people of color to testify at trials involving themselves, but in 1721 a change of law made this illegal. The right was returned in 1817, the year following Bussa’s Rebellion. The reason for the change is thought to be due to the need for a “reward” for no small number of the free colored people who sided with the whites and helped suppress the rebellion.

(Note 7) Taken from British abolitionist George Pinkard’s book “Notes on the West Indies”, 1806.

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.8.28 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 16"

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.4.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"416th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.3.13 UPDATE

EVENTS

"415th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.2.20 UPDATE

EVENTS

"414th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.2.12 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 15"

- 2025.1.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"413th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.12.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"412th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.12.4 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 14"