Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 13)

Section 7 The Path to Abolishing Slavery (Cont’d 2)

(Methodist Missionary Shrewsbury)

Reaction of the Church to the Abolitionist Movement

In Barbados where the new social class was emerging, how did the Christian Church, whose teachings proclaimed “equality of all people before God ” react the situation where the world was steering towards the abolition of slavery?

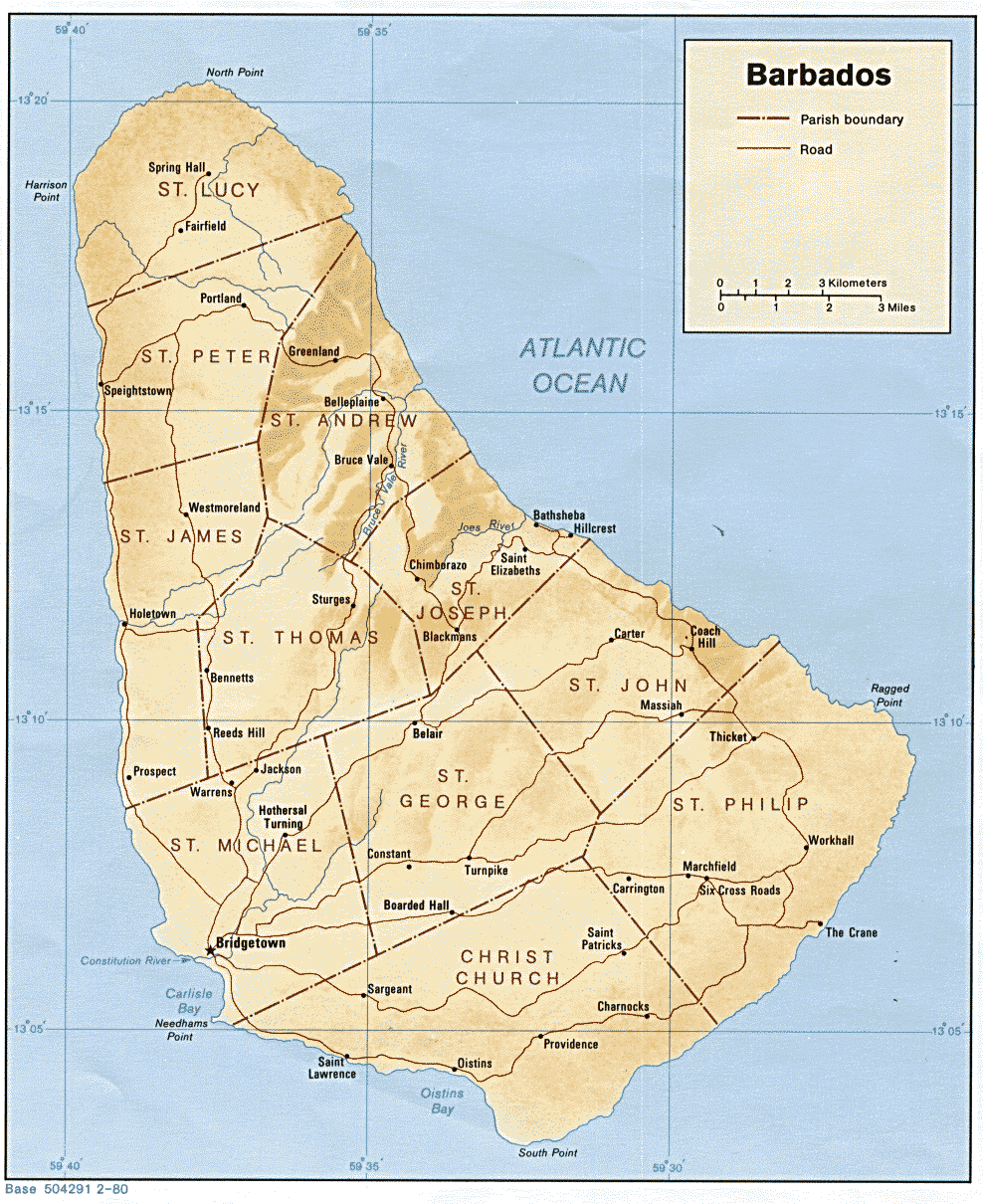

Among the Caribbean colonies, British influence was the strongest in Barbados, with the colony even being dubbed “Little England”. There is no denying that the denomination which held the most power in “this island Little” was none other than the Church of England. The island was divided into eleven parishes which served as the basic governing units for the local colonial authorities.

Generally speaking, the Anglican Church was apathetic to the Christianization of slaves and non-whites for a long time, and took a cold and indifferent, if not downright oppositional, stance against the abolition movement. This is not hard to imagine as the Anglican Church’s base was composed of conservative colonial authorities and plantation owners who made a living off the labor of the enslaved Black population.

I previously mentioned that in the late 17th century the founder of the Quakers, George Fox, visited Barbados admonishing the evils of slavery for which he was consequently driven off the island. Following Fox, Moravian, Baptist, and Methodist missionaries occasionally visited the island with hopes of Christianizing as well as improving the treatment of slaves.

The first people to speak out against the inhumanity of slavery in the threshold of the domination of the Church of England associated with the colonial ruling class were Nonconformist Protestant missionaries.

(The 11 parishes of Barbados)

One of these missionaries was a Methodist pastor named William James Shrewsbury (1795 – 1866).

The Methodists, who came onto the scene in England in the middle of the 1700s, were a branch of the Protestants who valued the “methodical” lifestyle, of which I am far from living, leading a disciplined life, even forgoing alcohol and tobacco. They were also passionate about the baptizing of slaves and improving the lives of the poor.

Shrewsbury, who arrived in 1820 on Barbados at the age of 25 met a woman of 18 named Hilaria King.

Hilaria was from a fairly wealthy family who belonged to the Anglican Church. However, she converted to Methodism after listening to Shrewsbury’s preachings. The two became close and eventually married, with the promise that she would relinquish the inheritance to be left to her, as her family made a fortune thanks to slavery.

During his missionary activities in the island, Shrewsbury was shocked by finding the slaves lived. He sent the following letter back to the Methodists’ London Headquarters, giving a scathing review of what he saw.

“The fear of God is hardly to be seen in this place. The free black people who live in town are, many of them, exceedingly given to profanity, especially the watermen; for they swear and blaspheme the name of God almost with every breath…As regards the moral condition of the slaves, that is nearly the same; polygamy, adultery, fornication, blasphemies, theft, lying, quarrelling, and drunkenness—these are the crimes to which the generality are addicted. They live and die like the beasts of the earth…We are happy, however, to find a few honourable exceptions.

“The island is divided into eleven parishes, and there is a church erected and a clergyman appointed to each; but it is a rare thing to see a slave within the church walls…Not that they are prohibited from going to church—the clergymen would be glad to see them attend; but no man compels, no man invites them to come in. They are lost, and no man goes to seek and save them; they are as much disregarded and neglected as if they possessed no immortal souls.” (Note 1)

At the time, no small numbers of the enslaved women were treated as “the white master’s concubines”, ending up the man’s plaything. There were women who were influenced by Shrewsbury’s sermons, and fearing the punishment of God, ran away from their masters. This kind of development on the island caused friction between Shrewsbury and the island’s white ruling class.

In 1823, the contents of Shrewsbury’s letter to London made its way back to Barbados and was printed in the Bridgetown newspaper. This deeply hurt the pride of the island’s Anglican Church, and Shrewsbury soon became the object of the conservative class’s wrath. He was unjustly labeled such as “spy for the abolition movement” or “instigator of the slave revolt”, and became the target for cases of insidious harassment from his enemies.

The timing of this incident was also not on Shrewsbury’s side. In the exact same year, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies Henry Bathurst had sent a notice to its Caribbean colonies to observe the “Amelioration” policy for the slave population.

Even after the Slave Trade Act was passed, the treatment of the enslaved in the Caribbean did not improve in the slightest. The British government was displeased with the situation as well, and pressure from abolitionist groups to immediately emancipate the enslaved population began to increase. These circumstances are what forced the British government to issue a notice to enact this amelioration reform.

This notice included points that are considered outrageous in today’s world, such as outlawing the following actions: flogging of slaves in the fields to make them work harder, flogging of female slaves (which means it was legal to flog male slaves…), tearing apart slave families for sales, using slaves as collateral for loans, etc. However, the colonies’ ruling class considered their treatment of slaves to be fair, and also held the belief that treating their slaves “too well” would not lead to anything good. Thus, they frowned upon suzerain’ condescending instruction regarding the treatment of their slaves. This feeling was especially strong among Barbados’ high society, whose strong sense of pride took a large blow by the reforms.

Sure enough, slaves in Demerara, British Guiana, staged a large-scale revolt after hearing of the government’s notice. At this time, a missionary named John Smith who had been sent to Demerara by the London Missionary Society (Note 2) was charged by the local authorities of having planned the revolt and subsequently sentenced to death. Smith died while in prison from a high fever.

These series of events led the Barbadian conservatives to become wary of nonconformist activity on the island, afraid that they would give slaves the wrong idea about freedom. Their message in point-blank terms to these missionaries was “don’t meddle in other people’s affairs of which you have no knowledge of”.

The island’s conservatives formed a “Secret Committee for Public Safety” to plan an attack on Shrewsbury.

On October 19th the same year, the Committee gave orders to a group of white ruffians to attack the Methodist chapel Shrewsbury built in Bridgetown.

Shrewsbury’s wife, Hilaria, who was nine months pregnant, did not hesitate to literally stand in between her husband and his attackers, bravely claiming “you must get past me first if you want to get to the minister”. Shrewsbury must have undoubtedly been a person of virtue to be blessed with such a reliable spouse. This is something we should learn from.

Luckily neither of them was harmed, but the brick chapel was destroyed with no trace left behind.

Requests from the Shrewsbury’s to the Governor for protection after their dangerous ordeal were left unanswered. He and his pregnant wife fled Barbados a few days after to the neighboring island of St. Vincent, approximately 180 kilometers away. Three hours upon arriving at St. Vincent, Hilaria gave birth to a healthy baby boy who they named Jeremiah.

On the other hand, not a single member of the gang that destroyed the chapel in Bridgetown was punished for committing a crime.

Afterward, Shrewsbury moved to the British Cape Colony in South Africa where he continued his missionary activities for a long period of time. However, after Hilaria died of a miscarriage of their eighth child, William and his children moved back to Britain where he spent the rest of his life.

William Shrewsbury never returned to Barbados. But their first child Jeremiah, who was born immediately after their escape from the island, followed in his father’s footsteps and became a Methodist minister. Jeremiah went back to the island which caused his father much difficulty so as to carry out missionary activities.

Presently, a simple Methodist chapel bearing Shrewsbury’s name stands in the parish of St. Philip.

(Shrewsbury Methodist chapel located in the parish of St. Philip)

News of the persecution of nonconformist missionaries made its way back to England. John Smith’s death in prison in Demerara and the attack on Shrewsbury in Barbados were deemed shameful behavior on part of the colonies. The incidents were taken up in the House of Commons, spotlighting the violation of the freedom of religion and a disgraceful affair of the British colonies.

As things had come to such a state, a change had started to occur even within the “great” Anglican Church. Foreign Minister George Canning (later Prime Minister), who took the situation seriously, helped orchestrate a strengthening of the Anglican Church’s activities abroad.

Government subsidies for the Anglican Church substantially increased, and two new dioceses were created in the Caribbean. This was the Government saying “Everyone, the Church of England is the face of our nation. The government is here to support you, so please clean up your act for everyone’s sake.”

The two newly created dioceses were divided into the following jurisdictions: (1) Jamaica, Bahamas, British Honduras (present-day Belize), and (2) Barbados, Leeward Islands, Trinidad, and British Guiana. Young, competent bishops were dispatched from England to serve in each jurisdiction.

One of these bishops was William Hart Coleridge (1789-1849) who was dispatched to Barbados in 1825. He settled into the island, the headquarters for the new diocese and worked on the tasks of turning around the Anglican Church in the region as well as Christianizing the enslaved population.

Coleridge realized that shifting the mindset of the priests and plantation owners on the island should be done prior to christianizing the slaves. He stated the following in an address to the island’s clergy:

“I need not remind you that in every attempt of ours to ameliorate the spiritual condition of the slave population, we must, as much as possible, carry the influence of the planter along with us, ……Every soul is God’s property; every soul in your parish must be your care. The soul of the master, and the soul of the slave, will equally be required at your hands.”

The number of clergymen and chapels on the island greatly increased during the bishop’s stay on the island. Under the orders of Coleridge, the figurative lead salesman or “Ace” of the company who was sent from the Headquarters to motivate the struggling regional branch, his subordinates had no choice but to submit to orders whatever may come. Thus, the movement to Christianize slaves and non-whites visibly picked up speed.

Coleridge, who believed that early education was a crucial element in alleviating the ruling class’s “allergy” to enlightening the enslaved population, dedicated his efforts to expanding educational opportunities on the island. When he first arrived in Barbados, there were only eight schools with a total of 500 students. Among them, there were only two schools which allowed non-whites to attend, one of them being the previously-mentioned Codrington College.

However, around the time that the bishop’s tenure ended, more than 80 schools had been built, including church-affiliated schools (similar to ‘terakoya’, where temples offered public education to children in Japan), boasting a collective 7,000 students. Among these was a school which enrolled enslaved girls.

In 1831, a strong hurricane hit Barbados, inflicting great damage to churches’ and schools’ buildings that were predominantly made of wood in that time. Coleridge spent day and night tirelessly taking charge of the restoration work. His passion became legendary, being spoken of for years to come.

As a result of Coleridge’s hard work, Christianization of the enslaved population rapidly progressed. The slaves started to perceive that the Anglican Church cared for and valued them.

This is how the Church of England became the main denomination among the Black slave population. The days where slaves could freely enter churches and their children could go to school without hesitation were still years away, but the reluctance of the whites had comparatively eased since previous times.

Coleridge’s reforms to the island’s Anglican Church are part of the reason why there was little to no chaos when the slaves were freed after more than two centuries of being suppressed under the cruelties of slavery.

Coleridge noted the following about the day the slaves gained their freedom:

“800,000 human beings (Note 3) lay down last night as slaves, and rose in the morning as free as ourselves. It might have been expected that on such an occasion there would have been some outburst of public feeling. I was present but there was no gathering that affected the public peace. There was a gathering, but it was a gathering of old and young together in the House of the Common Father of all. It was my peculiar happiness on that ever memorable day to address a congregation of nearly 4,000 people, of whom more than 3,000 were Negroes just emancipated. And such was the order, the deep attention, and perfect silence, that you might have heard a pin drop.” (Note 4)

Coleridge, who helped guide the end of Barbados’ slavery to a soft landing, spent 16 years on the island before returning to England in 1841 due to illness, passing away the following year at the age of 60.

(Painting of Bishop William Coleridge of the Anglican Church. Photo by: Christ Church, University of Oxford)

Britain’s Slave Abolition Act came into effect on August 1st, 1834, emancipating all slaves throughout British Colonies, including Barbados.

At this time, compensations were paid out by the British government.

However, do not misunderstand. Money was not paid to the newly freed Black individuals who had endured the tortures of slavery, but instead tit was paid to former slave owners as compensation loss for “infringement on private property rights”.

The British government paid £20 million in compensation to former slave owners that is estimated to be approximately 20 billion USD in today’s value.

Barbadian slave owners received about £1.72 million. This equals a bit less than 10% of the total amount allotted to Britain’s Caribbean slave-owning colonies. Comparing its land area ratio of all of its Caribbean colonies, Barbados received much bigger ratio of compensation money. This calculation highlights the fact that Barbados’ prosperity was linked to its flat land, dense population, and large slave population which was confined to work-intensive plantations.

The compensation sum of £20 million was almost 40% of Britain’s annual national income at the time. The government was unable to procure such an amount at once, and thus it borrowed necessary funds from a few of private banks run by the nation’s wealthy.

One of these banks was a famous British investment bank “N. M. Rothschild & Sons Limited” which had been founded in the beginning of 19th century by Nathan Mayer Rothschild and is still in flourish business today.

The bank was picked up by the media in 2009 for its past dealings related to the slave trade, to which it responded immediately with the following press release: “We greatly regret the firm is linked in any way to the inhumane institution of slavery” (note 5).

The bank’s statement continued, stating that “Rothschild himself arranged a loan on behalf of the British government which accelerated the abolition of the slave trade by facilitating the payment of some compensation to slave owners” in a tone that cannot help but sound boastful. It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.

It was in 2015 that the British government finally finished repaying its creditors, including N. M. Rothschild & Sons, along with interest and handling fees. David Cameron was the British PM at the time. The source of funds for paying back these megabanks was taxpayers’ hard-earned money. There is no doubt that a large number of slaves’ descendants were also included as taxpayers.

Apprenticeship System-an Extension of Slavery

Though I previously mentioned that slaves were emancipated by the enactment of the Slave Abolition Act, there was in fact another hurdle to clear for slaves to attain “true emancipation”.

A new system called “apprenticeship” was introduced on the day when the slaves had supposedly become free.

Although the British government was finally able to abolish slavery in its colonies, there were multiple challenges that simultaneously appeared. Where will the newly freed slaves live? How will they make a living? How will sugarcane plantations make sure they have enough workers? Not to mention will it be okay to just open the door and let the freshly emancipated slaves, who have never worked anywhere else except plantations, walk out? How can we be sure public peace won’t be disturbed?

The answer the British government worked out to these worries was the apprenticeship system.

This system used apprenticeship as a way to keep former slaves on the plantations for a fixed time, which was not only supposed to help secure workers, but also “help emancipated slaves master skills, learn common sense and sense of responsibility as free citizens” needed when looking for jobs after their term was over.

Implementation of the apprenticeship system was left to the discretion of each colony to a certain degree, but these were the common conditions:

・All physical bondage will be permanently abolished

・All slaves six years old and under will be immediately and unconditionally freed

・All slaves seven years and over of age will be employed under the apprenticeship system. The term for field workers will be six years; domestic workers four years

・Apprentices will work 45-hours per week; 3/4 of this time will be devoted to free service on plantations. There will be no work on Sundays

・Apprentices are free to work for wages on other plantations, work as day laborers, rest, and otherwise spend their free time however they choose

・It is possible for apprentices to purchase their freedom for a fixed price before their period of apprenticeship is completed

・Special magistrates hired by the British government will be appointed to each colony in order to assure proper implementation of the apprenticeship system

After analyzing the conditions of apprenticeship, I couldn’t help but think to myself “Wait a minute, Forgetting bondage and child labor, a 45-hour work week with Sundays off is a much better working environment than all my years spent working in the Kasumigaseki government office district in Tokyo…there were times where I even put in over 100 hours of unpaid overtime every month!” However, it may be disrespectful to compare the grueling work these ex-slaves undertook in plantations versus my time in the office.

At any rate, this system forced emancipated slaves to work without pay during most of working hours as an “apprentice” under the pretense of on-the-job training.

From the point of view of former slaves, this new system was obviously nothing more than slavery in a different form, meaning “Now that we have our freedom, we need to find an employer who will pay us the highest, and who won’t make any outrageous demands or make us work overtime”.

On the other hand, rather than take care of and pay for the emancipated slaves’ basic necessities such as shelter, clothing, and food, plantation owners considered it more cost-effective to hire them as wage laborers as needed. In other words, it was cheaper to hire temp staff rather than spend necessary expenses on retaining permanent employees.

In other British Caribbean colonies which had larger land area such as Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana, there was still a large amount of uncultivated land that remained, thus freed slaves could go out and start their own farms. There was also the chance to start a business related to crops distribution channels, as a wide variety of crops apart from sugarcane were cultivated in these colonies. Therefore, in larger colonies there was some meaning to the apprenticeship system as it acted as a buffer period during which the ex-slaves were able to learn a new trade.

On the other hand, the apprenticeship system had little meaning for colonies such as Barbados where the land area was limited relatively, leaving few options for freed slaves other than to work on sugarcane plantations. (St. Kitts, Antigua, and other small colonies were in the same boat, and so in particular Antigua the apprenticeship system was not applied.)

Under this situation, complaints and petitions flooded the special magistrates -in other words the labor standards inspectors-who were there to watch over the indentured servitude system, coming from both plantation owners and apprentices. This caused apprenticeship system for both field and domestic workers to be abolished in four years.

When slavery was abolished four years prior, the slaves welcomed the day unbelievably quietly. However, when the apprenticeship system ended on August 1st 1838, they danced and sang about in the streets celebrating their true emancipation.

The African-Barbadian slaves were finally freed of their yokes. However, what was waiting for them was anything but a field of flowers (note 6).

The ex-slaves, who until now had only lived on plantations and worked under a white “master” disregarding their own volition, were, without enough education and training, suddenly thrown into the rough seas of modern capitalism where labor force is treated as a commodity that is bought and sold.

So, they took destiny into their own hands and began carving out their own future on this colonial island.

(The Drax Hall Estate built in the middle of the 17th century. Photo by Colonial Architecture Project)

There was an article from the Barbadian newspaper “Saturday Sun” dated December 19th 2020 titled: “Drax Hall owner against repatriations.”

Richard Drax, a Conservative Member of Parliament, has been facing heat both here, in Jamaica and Britain from people who are demanding that he pay reparations for dagames done by slavery at the 621-acre Drax Hall estate, said to be the first sugar plantation in British empire almost 400 years ago and worth an estimated £4.7 million (about BDS $12.5 million). However, Drax, 62, who was featured in several British media outlets this week, is not so inclined. Reporters indicated that his father died in 2017 and he inherited the plantation which he has also registered in his name and pays the taxes. Drax Hall is the oldest house in the Western Hemisphere and was built around 1650, 20 years after his father James Drax first sailed to Barbados.

According to a report in the Daily Mail, Drax, the South Dorset MP whose ancestors operated the plantation from 1640 to 1836, said* “ I am keenly aware of the slave trade in the West Indies, and the role my very distant ancestor played in it is deeply, deeply regrettable”. “But no one can be held responsible today for what happened many hundreds of years ago. This is a part of the nation’s history, from which we must all learn”.

Chir of CARICOM’s Repatriations Commission, Professor Sir Hilary Beckles, who is also Vice-Chancellor of the University of the West Indies(UWI), was quoted in the Sunday Mirro as calling on Drax to do the right thing.

He said:“Black life mattered only to make millionaires of English enslavers and the Drax family did it longer than any other elite family. When I drive through the Drax Hall land I feel a sense of being in a massive killing field with unmarked cemeteries. Sugar and black death went hand in glove.” “ it’s no answer for Richard Drax to say it has nothing to do with him when he is the owner and the inheritor. They should pay reparations.” He added that “ the people of Barbados and Jamaica are entitled to reparation justice.”

He estimated 30,000 enslaved people had died in Barbados and Jamaica due to the Drax family trade.

…Richard Drax, a father of four, was previously criticized by political rivals for “hiding his aristocratic roots” by not using his quadruple-barrelled name in 2009.

The former army officer and BBC journalist is the largest individual landowner in Dorset, with 13,870 acres , and is worth an estimated £150 million. He owns Charborough House in Dorset and holds the lordship of the manor of Longburton.

The “reparation movement”, which demands descendants of plantation owners, colonial suzerains etc. pay compensation for what their ancestors did in the past, has become more active in recent years in the Caribbean.

James Drax mentioned in the article settled in Barbados in the beginning of the 17th century shortly after the island became an English. He built his estate, Drax Hall, in the center of the island in St. John’s Parish.

Drax Hall is well-known not only in Barbados but throughout the Caribbean for being one of the richest sugarcane plantations which used a vast number of slaves. So, his name frequently appears in Barbadian history books as the pioneer of the sugar industry and as the successful plantocrat. The reason Jamaica was mentioned in the article was most probably due to the fact that the Drax family also had colonial businesses in Jamaica.

Richard Drax, who was being targeted in the article, is a direct descendant of James Drax and is currently a member of the House of Commons. He, instead of quickly letting go of his inherited plantation property in Barbados, his possession of the site has turned out to be a source of criticism (note 7).

“Why does he have to pay reparations for his ancestors who used slaves on their plantations hundreds of years ago…?” I can’t say I don’t feel sorry for this British multi-millionaire, but the scars of those affected by slavery are no doubt deep.

The CARICOM Reparations Commission (CRC) was founded in 2013 to pursue the responsibilities of Britain and other European nations who gained immense wealth from exploiting and ill-treating African slaves and to demand them to pay reparations.

However, as it can be easily imagined, the roots of this problem are too deep and too entwined. So, thus there is currently no concrete direction regarding how to determine who, in what country, is responsible for paying for what extent of reparations in what form to whom.

Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, called on the UK and EU regarding reparations:

“There must first be an apology and an acknowledgement that wrong was done and that successive centuries saw the extraction of wealth and the destruction of people in a way that must never happen to any society or any race in this world again” Mottley also pressed for acknowledgement by the colonisers of their obligation to give assistance to a Caribbean the left in very dire social and economic circumstances (note 8).

(To be continued in Part 8 Trailblasers of Destiny)

(Note 1) "The History of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society", Findlay and Holdsworth, 1924

(Note 2) The London Missionary Society was established in 1795 with the main sponsorship of the Congregationalist Church, a denomination of Protestantism.

(Note 3) The number 800,000 was probably the number that Coleridge recognized as the total number of emancipated slaves throughout the British West Indies. However, in the reality the number is presumed to be around 670,000

(Note 4) “Barbados Diocesan History”, p. 38

(Note 5) Reuters, July 1st 2009

(Note 6) Slavery in British colonies was abolished; however, it was in no way the case that the British awakened to the idea of “universal human love”. For example, Britain was bringing massive amounts of Indian-grown opium into China around this time, drugging the population. When the Qing dynasty government started to crack down on the opium trade, Britain reacted by starting a war (Opium Wars, 1840). Britain easily pushed back China, leaving the Great Powers to divide it into a semi-colonized state. This is an example of what the British people were doing on the opposite side of the world at just about the same time as when Britain was proclaiming its “humanitarianism” with the abolishment of the slavery. As we know, in the latter half of the 1800s, the division and colonization of Asia and Africa by Britain, France and other Western powers started to pick up pace. The finishing touches on their control and exploitation of different races and religions took place during this time.

(Note 7) In addition to Richard Drax, the Oscar-nominated British actor Benedict Cumberbatch has also come under fire from reparations movement organizations after it was revealed that his ancestors also owned a sugarcane plantation in Barbados. Cumberbatch’s ancestors ran a plantation on the island’s northeast St. Andrew parish from the beginning of the 18th century, possessing a large number of slaves to work on the property (Sky News December 21, 2022).

(Note 8) Taken from an article in the Barbados daily newspaper Nation, July 7th 2020

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2024.12.4 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 14"

- 2024.9.17 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 13"

- 2024.7.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"408th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.7.23 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 12"

- 2024.7.9 UPDATE

ABOUT

"GREETINGS FROM THE PRESIDENT JULY 2024"

- 2024.7.4 UPDATE

EVENTS

"APIC Supports 2024 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2024.6.27 UPDATE

EVENTS

"407th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.5.21 UPDATE

EVENTS

"406th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.5.14 UPDATE

EVENTS

"405th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.4.2 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Water Tanks Donated to Island of Wonei, Chuuk, FSM"