Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 14)

Section 8 Trailblazers of Destiny

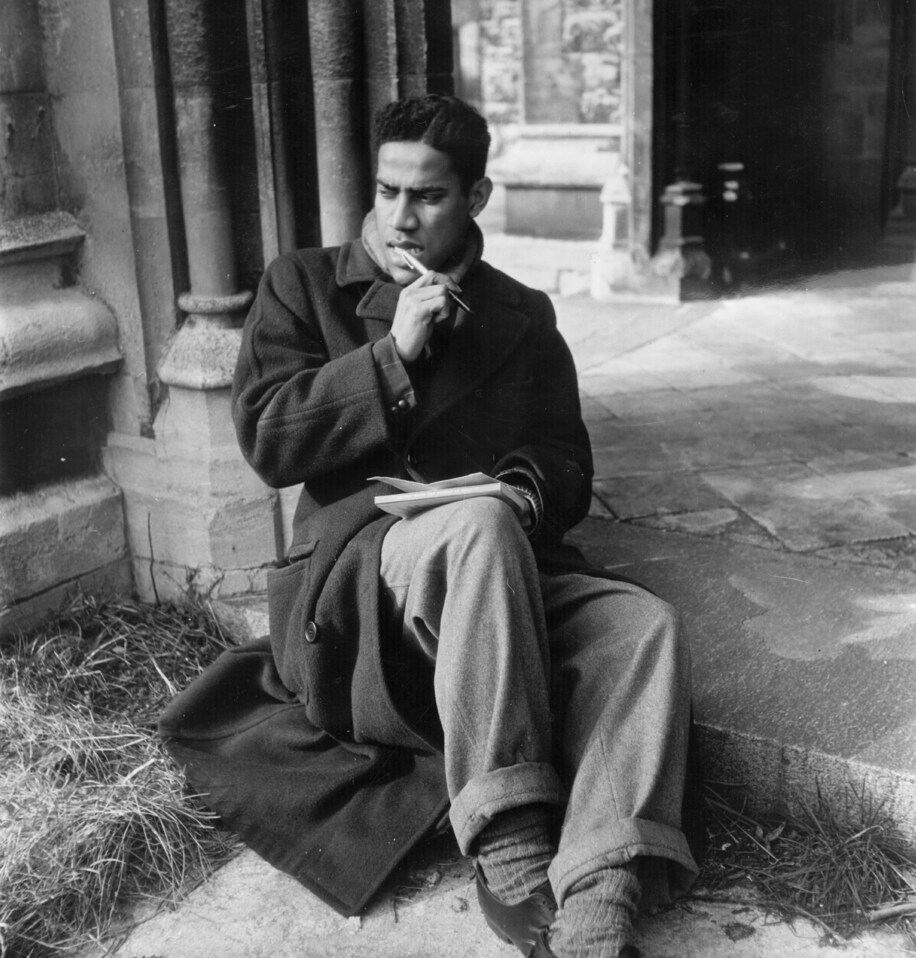

(young George Lamming, one of Barbados’ most famous writers)

One of the masters of Caribbean literature is novelist George Lamming (1927-2022) of Barbados.

After graduating from a high school in Barbados, Lamming made his way to Trinidad and Venezuela, eventually ending up in the UK. His debut novel, “In the Castle of My Skin” which was published in London 1953 received positive praise and earned him the Sommerset Maugham Award, cementing its place as one of the masterpieces of modern Caribbean literature (note 1).

Lamming was born to a Mulatto mother and a white British father. “In the Castle of My skin” is an autobiographical novel looking back on his youth.

He describes his parents in the following manner:

>> My father who had only fathered the idea of me had left me the sole liability of my mother who really fathered me. And beyond that my memory was a blank. It sank with its cargo of episodes like a crew preferring scuttle to the consequences of survival…<<

>> She (my mother) had never lost the fine brown freckles which were hardly visible. Her nose was like a brief index finger pointing downwards, sharp and straight and strong…She was what they called a very fair mulatto.<<

The novel starts with its protagonist -- little Laming -- as a nine-year-old boy (by looking at Lamming’s year of birth, the setting is 1936). He lived with his mother in a small village outside of Bridgetown where people of African descent lived. The beginning of the story reflects on his elementary school days and his many unique neighbors - letting the readers get a glimpse of poor but peaceful life of ordinary folks of the island.

Looking down at the village from on top of a hill there was a splendid mansion where a landowner of the village and surrounding properties lived with his family. The simple houses which the villagers lived in were owned by this landowner, and villagers had to pay him a monthly rent. In addition to being a plantation owner, the land owners also owned a shipping company. Many villagers were employed by the company as dockworkers in the Bridgetown port.

>> From any point of the land one could see on a clear day the large brick house on the hill. When the weather wasn’t too warm, tea was served in the wide, flat roof, and villagers catching sight through the trees of the shifting figures crept behind their fences, or stole through the wood away from the wall to see how it was done…<<

>> Once a quarter or after some calamity like the flood, the landlord with his family drove from road to road through village. He inspected the damage, looking from one side of the road to the other. Those who were untidy scampered into hiding, much to his amusement, while the small boys who were caught unawares came to attention and saluted briskly. The landlord smiled, and his wife beside him smiled too. The daughter seated in the back of the carriage looked down haughty and contemptuous. <<

The protagonist lived a humble life with his mother who taught at a Sunday- school of the village church. He spent his days carefree playing with other neighborhood mischievous boys until one day a small incident involving the landowner’s daughter cast a dark cloud over the villagers. This was a sign of drastic changes that Barbados was heading for.

The novel follows the protagonist as he grows up with the boyish questions and worries, always aware of the one thing that can never be changed - the color of his skin.

*********************************************

Prescod, the Pioneer

Just as George Lamming had depicted, economic domination by the whites continued long after emancipation. The biggest factor behind why the whites (the minority) held economic power over those of African descent (the overwhelming majority), who were living in close to extreme poverty, was the problem of uneven distribution of land.

All of the UK’s colonies in the West Indies were in the same predicament. However, Jamaica, Trinidad, British Guiana (now Guyana), and other large colonies had a surplus of land, which gave non-whites a better chance to buy cultivable land. However, it was difficult for free non-whites and emancipated slaves to buy land on the smaller islands such as Barbados, Antigua, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent, limiting the roads to economic independence. Due to this, class differences on those islands were strikingly obvious.

After emancipation and the abolition of the apprenticeship system, the “Located Labourer System” enabled the island’s oligarchy - the white land owners - to have a monopoly on economic rights.

The Located Labourer System allowed ex-slaves to continue living on the land and in the houses they did before as slaves, in exchange for paying rent to landowners, as well as working five days a week on plantations. This differs from the apprenticeship in that they were paid a fixed salary for their labor, but was 20-30% less than what they would receive on the free labor market.

The Located Labourer System was put into place based on the suzerain UK’s 1840 “Masters and Servants Act”. The Act systemized the exploitation of non-white labor after the abolition of slavery. It maintained its efficacy nearly 100 years, until right around the beginning of World War II.

This System, which was created in order to secure a stable labor force at plantations, included the right for landowners to arbitrarily evict laborers from their homes, together with other family members. It allowed landlords to give four weeks’ notice of eviction to tenants whom they deemed “workers of unsatisfactory performance”.

Under such a system, cogs start to grind in the mind of workers: either slack off where they can’t be seen, or seek better treatment and leave for better prospects. The aftermath of the effect which plantations had during slavery were prolonging this situation. In no way was it contributing to society’s stable development nor to the welfare of the majority of the island’s residents. In fact, a large number of ex-slaves and their descendants left the island in the second half of the 19th century.

The first person who openly raised an objection to this situation in Barbados was Samuel Jackman Prescod (1806-1871).

Prescod, who was the editor at the progressive newspaper “Liberal”, noticed that the wealthy white landowners furtively and rapidly bought up Barbados’ surplus land after the end of the apprenticeship system when slaves were completely emancipated, which caused land prices to soar. Buying up land was the most effective method to prevent non-whites from owning land and creating a middle-class, threatening the existing order of the white ruling class.

In 1840, Prescod submitted a document detailing his complaint to the local authorities against this newfound truth. The authorities conducted an investigation, bringing to light the problematic business that had fueled soaring land prices. However, no effective measures were put in place as it would require legal action, because the Barbados parliament at that time was comprised solely of white men.

Prescod’s mother was a free person of color, and his father was a rich white landowner. Prescod did not receive regular higher education, but studied literature by himself, writing poems and play scripts in his early 20s. His works, which sharply depicted the discrepancies of Barbados society, gained popularity, not only from non-whites but also from lower-class whites as well.

After the abolition of slavery, Prescod became the Editor-in-Chief of the “Liberal”, amping up efforts to help improve the treatment of non-landowning poor non-whites. With the failed attempt to try and gain the understanding of the local authorities and the Parliament in regards to the matter of soaring land prices, Prescod ran for a seat in the Barbados House of Assembly from the Bridgetown constituency. Against all predictions, Prescod won, becoming the first non-white Assembly member. His win was the result of the majority of non-white middle-class voting for him at a time when suffrage was severely limited to those above a certain income.

Prescod was continually elected for over 20 years. During this time, he formed the “Liberal Party”, raising his voice for franchising reform and for increasing educational opportunities for people of African descent.

However, he was outnumbered. Prescod’s political arguments tended to turn radical, which resulted in only a small number of his efforts to be enacted by the wealthy white majority of the Assembly. Yet his presence on the island, where slavery had just ended, gave hope to the future for the non-ruling class.

Prescod was posthumously named a “Barbados National Hero” in 1998 as the first non-white to participate on the political stage in Barbados. Additionally, his portrait is featured on the 20 Barbadian dollar bill.

(Samuel Jackman Prescod portrait featured on the 20 Barbadian dollar bill)

The same contradictions and friction which occurred in society after emancipation, as evidenced by Prescod’s lonely battle in Barbados, could be seen in other British colonies in the Caribbean as well.

In 1865, a revolt in Jamaica by residents of African descent turned into a large-scale rebellion. The rioters, who were fed up with the lack of suffrage and of improvements in their living standard, stood up and clashed with the whites, turning the situation into a civil war. The riot was suppressed by the white vigilante corps and the resident British army, with over 400 African-Jamaican lives lost. The uprising, named “Morant Bay Rebellion” (taken from the place where the riot occurred, Morant Bay), or the “Jamaica Incident”, divided public opinion in the suzerain, Britain.

The British government came up with a plan after seeing public dissatisfaction and unrest continue to increase in other colonies of the West Indies.

This was the era of Queen Victoria (reign: 1837-1901), the peak of the British Empire which controlled over the seven seas and maintained colonies in all corners of the world. What the UK, feeling smug with its power, did for the improvement of the situation in the West Indies was not the franchise enlargement for the colonial residents which would reflect the majority opinion. What the UK did instead was to designate them Crown Colonies (note 2), abolishing public elections for colonial assembly members and replacing them with the Crown nominee system.

The logic behind this move was that “a select few of the wealthy class cannot understand what the majority of the other residents want. Thus, in order to protect the benefits of the ‘woeful lower-class’, it is in the colonies’ best interest to take away the right to vote from the wealthy and give it to the wise and merciful Crown to govern the colonies directly”.

Starting with Jamaica of the Morant Bay Rebellion, Dominica, St. Kitts, Nevis, Montserrat, British Honduras (now Belize), Grenada, St. Vincent, and Tobago were made Crown colonies. Their Lower Houses, which had until then been elected by the citizens, were abolished, leaving the Upper Houses whose members were nominated by the British government, becoming a unicameral system.

The only colonies that retained a citizen-elected Lower House until 1875 were Barbados, Bermuda, and Bahamas.

Governor Hennessy and the Confederation Crisis

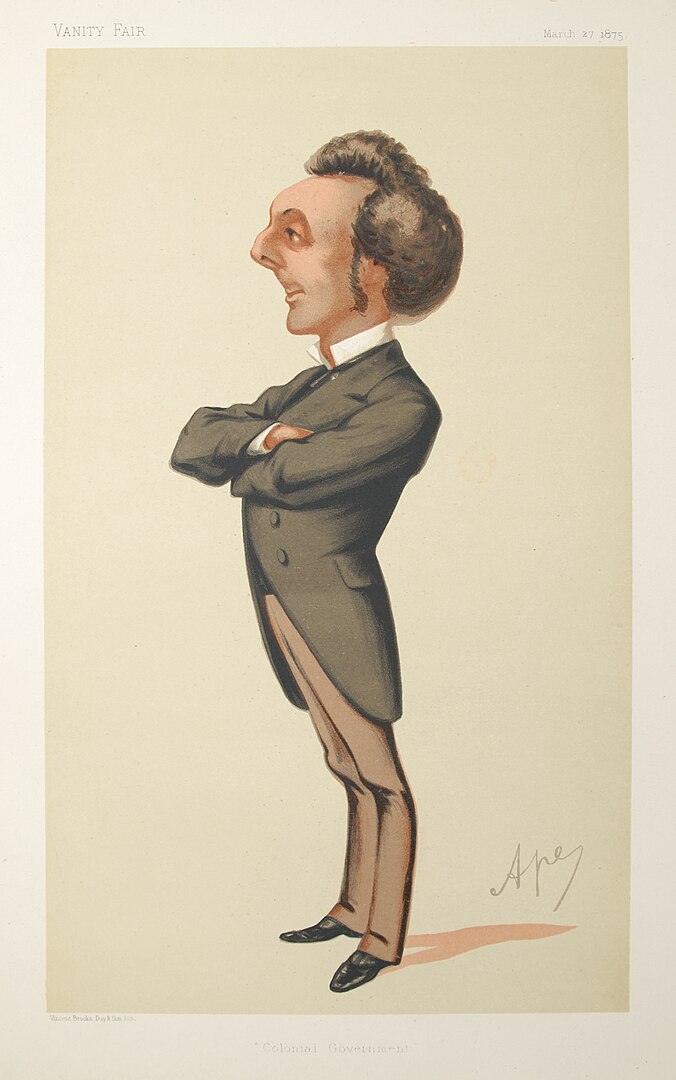

There was concern among Barbados’ ruling class that the island would eventually become a Crown colony and subservience to the suzerain would be strengthened. In the midst of this, a newly appointed governor from the British Colonial Office, named John Pope Hennessy (1834-1891), made landfall on Barbados in November 1875.

Hennessy was of Irish Catholic descent, rare for a high-ranking official of the U.K. at the time. This fact made Barbados’ ruling class’s wary of Hennessy’s presence, as the majority was of English descent who belonged to the Anglican Church. Hennessy also openly listened to the opinions and complaints of the African-Barbadians and Mulattos, which only heightened the white old guard’s distrust towards the new Governor.

During these tense times, early on in his appointment Hennessy abruptly made six proposals to the Barbados House of Assembly.

The contents were as follows:

> ① The Auditor of Barbados should be appointed by Auditor General of the Windward Islands.

> ② The power of transporting prisoners from Barbados to other islands and receiving prisoners from the other islands should be secured to the Government-in-Chief.

> ③ The new Lunatic Asylum should also be open for the reception of lunatics from the other islands.

> ④ A similar arrangement should be made about a common lazaretto.

> ⑤ There should be a Chief Justice of the Windward Islands and a remodeling of the judicial system based on the necessity of centralizing it.

> ⑥ There should be a police force for the Windward Islands.

Some explanations for the above would be needed. In fact, in 1833, long before Hennessy was appointed Governor of Barbados, the Governor of Barbados had been given jurisdiction over the neighboring British colonial Windward Islands (note 3) which included St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenadines, and Grenada. This was a measure that the suzerain put in place keeping in mind the abolition of slavery in the near future, as well as a way to strengthen and optimize its rule over the colonies. When Hennessy was appointed governor 30 years after emancipation, he was instructed by the Colonial Office to start working to create a “colonial confederation”, which would unify Barbados and the Windward Islands.

The island was trembling with fear after seeing these six proposals. Members of the upper class who were close to Hennessy and were involved in the suzerain’s colonial bureaucracy were allies of the Governor. However, the native white wealthy class, such as plantation owners, business owners, adamantly opposed the new proposals. Hennessy was labeled a “hypocrite who pretends to befriend the poor” by the local conservative paper.

The native wealthy class started to sniff out the plan to unify Barbados and the Windward Islands under the Confederation after seeing Hennessy’s proposals. From their point of view, they flat-out did not want to be grouped together with a bunch of lower ranking poor islands and eventually become a Crown colony like them, so submissive to the suzerain.

Although Barbados’ economy was in a slight decline, in former days it was one of Britain’s most prosperous colonies due to the sugar industry, even being dubbed “Little England”. The pride of the ruling class was considerable, and there was a tendency to look down on the neighboring small islands (I cannot say for certain that this tendency no longer exists in present-day Barbados…).

Putting pride aside, the ruling class was afraid of not only having their tradition of relative autonomy, which had been maintained by their Assembly, taken away by the Confederation, but they also feared the outflow of wealth and plantation labor force to other islands.

Then trouble started unexpectedly.

On April 18th 1876, on the grounds of the Byde Mill plantation straddling the three southeastern parishes of St. Philip, St. John, and St. George, two brothers of African descent by the surname of Dottin, started wielding around a sword and a sugarcane stalk with a red flag tied on the end. When they ran away from the authorities closing in on them, they sounded a warning through a conch shell. Then, all of a sudden, African-Barbadian workers in the nearby fields rose up together and started a rebellion.

The rebellion expanded in size to include around 1,000 people, colliding with police. The riot was named the “Confederation Crisis”, lasting for around one week, and resulted in eight African-Barbadian lives lost and over 30 people injured before it was suppressed.

The sole injury on the white side was the chief inspector of police. However, the whites who remembered the violent uprising of Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica were in quite a panic. Hundreds of whites temporarily took refuge in ships moored in Carlisle Bay and in the British army barracks of Garrison Savannah during the riot.

What caused the rebellion? The truth behind the reasons has still not come to light even after all these years.

Regarding the concept of the Confederation of Barbados and the Windward Islands, what would today be called “fake news” spread its way through the island, with baseless claims such as “the confederation will bring back slavery” or “land will be allotted to the lower class”, etc. reaching the ears of the masses. The general public was driven into a state of confusion over the fear of not knowing what was taking place. According to the investigation done by local authorities after the suppression of the riot, the majority of the African-Barbadians who partook in the rebellion did not know the meaning of the word “confederation”.

Interestingly, however, many African-Barbadians supposedly thought that “the merciful ruling Crown dispatched Governor Hennessy, a high-ranking official who listens to what we have to say, therefore it is unlikely that he would do anything bad for us”. Or, “if the plantation owners are so forcefully against the confederation, then there must be something good in it for us”.

There were various conspiracy theories regarding the rebellion: the anti-confederation force unleashed chaos on the island and tried to destroy the idea of the confederation; on the contrary, pro-confederation supporters tried to instigate the African-Barbadian population to pressure the native wealthy class and Hennessy was the puppet master in the background pulling the strings; etc. However, the truth still lies in the dark. In any case, there is no mistaking that the background of this uprising lies in the buildup of dissatisfaction of former slaves and their descendants whose treatment and lives did not improve in the slightest since emancipation. Under such circumstances, social anxiety for what the confederation would bring caused the rebellion.

As a result, the riot worked against Hennessy and his efforts to push on with the confederation. The island conservatives appealed to the British government for Hennessy’s discharge by saying his unnecessary actions created a chaos which led to deaths. At first the Colonial Office in London tried to conciliate with the anti-Hennessy faction. However, they could not deny that his methods were too haste and coercive, and thus they were unable to defend him any longer. In the end, Hennessy was relieved of his post as Governor of Barbados and was sent to the British colony of Hong Kong to assume the position of Governor.

This is how the attempt to create a confederation of Barbados and the Windward Islands failed. And the original concept of a confederation eventually disappeared too. In 1885 the joint jurisdiction that the Barbados governor previously had over the Windward Islands also came to a halt, and the Governor of Barbados returned to Barbados-only governing system. This system remained in place until Barbados’ independence in 1966.

(A political cartoon of Governor Hennessy in a British magazine, 1875)

Hennessy and Meiji Period Japan

From the conservative Barbadians’ view, they felt Hennessy’s transfer to Hong Kong, some far - off corner of the world, was well-deserved. However, Hennessy took a positive view and told everyone around him before leaving the island that his transfer to Asia was “a promotion”.

Hennessy was an interesting man. Prior to his post in Barbados, he had been appointed governor of other British colonies such as the Bahamas, Sierra Leone, and Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). All of these posts, however, only lasted one to two years. Looking at other governors appointed by the Crown, their tenures lasted for an average of three years, sometimes even five to six, including governors of Barbados.

As for Hennessy, however, it seems that his overly-enthusiastic attitude toward work coupled with an impulsive, slightly overbearing personality and lack of ability to read the room caused trouble during each of his assignments, leading to comparatively short terms as governor in each colony (there are people like this in any workplace). Although I admire the open-mindedness of the British Empire’s Colonial Office which continued to appoint him colonial governor, I have suspicions that London used this Irish outsider to do the government’s “dirty work”.

After his bitter experience in Barbados, Hennessy seemed to enjoy his post in Hong Kong, even receiving a name written in Chinese characters (軒尼詩). One of his legacies was mandating English language education in Hong Kong public schools.

Hennessy also had a connection to Meji-era Japan. In 1879 (12th year of Meiji), he boarded a ship from Hong Kong to Japan and spent two and a half months holidays. His official attendants during his stay in Japan were then Minister of Finance, Shigenobu Okuma and the Minister of Public Works, Kaoru Inoue. Especially, Okuma, who accompanied Hennessy throughout his visits even to Tohoku region, northeast of Honshu, might have heard stories of Hennessy’s hardship during his time in Barbados.

On a side note, one of the major problems the Meiji-era Japanese government was dealing with was the issue of revising unequal treaties made with Western powers, including Britain.

During his visit to Japan, it is most likely that high-ranking officials like Okuma and Inoue tried to instill Japan’s dissatisfaction on this issue into Hennessy. Consequently, he sent two letters to his mother country from Japan, addressed to Foreign Secretary Robert Cecil Marquess of Salisbury (Conservative), and former Prime Minister William Gladstone (Liberal). In his letters, Hennessy described Sir Harry Parkes, the British Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan, who had taken an especially stubborn standpoint opposing the revision of unequal treaties, that his “arrogant and disdainful attitude was not profiting the British Crown”.

It is true that Parkes’ disdainful and irreverent attitude gave him a poor reputation among Japanese officials. So, Hennessy’s opinion was not altogether off. But, Parkes was a diplomat and thus answered to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Governor Hennessy was an official who belonged to the Colonial Office. The two men belonged to different jurisdictions, which means Hennessy dared to meddle in other people’s business.

Parkes had already served as the British Envoy to Japan for 14 years at this point, and thus Hennessy’s direct criticism of Parkes addressed to powerful politicians at home can be regarded as Hennessy using his full eccentric potential. However, Parkes would continue to serve another four years in Japan before moving on to serve as Envoy to China (the Qing Dynasty), thus rendering the influence Hennessy’s remarks had on Parke’s career dubious (note 4).

Conrad Reeves, A Man of Compromise

Let’s go back to our subject.

Conrad Reeves (1821-1902) came in and cleaned up the mess of the Confederation Crisis that the former Governor Hennessy had made in his hasty actions.

Reeves was the illegitimate child of a white father, apothecary, and a black mother. He was able to receive a high level of education considering the time, and aimed to be a journalist, working at the newspaper “Liberal” which the previous-mentioned Samuel Jackman Prescod was the editor of. In other words, Reeves was under the tutelage of Prescod.

After being exposed to liberal ideas under Prescod, Reeves was offered the chance to go to Britain and studied law at Middle Temple, becoming a lawyer. After amassing his wealth as a successful lawyer in Britain, he decided to return to the Caribbean, starting with a post as Attorney General of colonial St. Vincent. In 1874 he returned to his homeisland Barbados and became a member of the House of Assembly, while simultaneously assuming the post of Solicitor-General of Barbados. He was one of the few non-whites to reach an elite position in colonial society.

The Confederation Crisis happened right at this time. At the onset of the crisis, Reeves stepped down from his position as Solicitor-General and became one of the leading members in the anti-confederation league. Taking a different approach from the African Barbadians in using violence against this “confederation”, on the surface it seemed that Reeves was siding with the wealthy conservative old guard.

Once the fatal Confederation Crisis had calmed down, Barbados colonial authorities presented the “Nominee Bill” that would replace the House of Assembly’s public elective system with a Crown nominee system. This was the suzerain’s way of further enforcing their intentions on the Barbadians. Reeves saw the introduction of this bill as a threat to Barbados’ autonomy, and fought against the bill to dropped on the grounds that Barbados would become the Crown colony.

In 1881, Reeves, with the cooperation of the second governor after Hennessy, William Robinson, busied himself with creating a new law to establish an “Executive Committee”. While the governors sent from the suzerain Britain to Barbados ruled largely to this discretion, this Committee was intended to cement the executive branch of government with legal backing, and would be the prototype for the future colonial government.

Until this point, Reeves’ career had mostly helped benefit the island’s conservative oligarchy.

However, Reeves, as a mulatto himself, knew that if he did not do something for his fellow people of color, the situation could not be reasonably managed. In 1884 he ardently persuaded the House of Assembly to introduce a Suffrage Expansion Act which lowered the income level necessary to obtain the right to vote. The Act was far from universal suffrage, but it opened the door for more non-whites to participate in the island’s politics.

Seeing Prescod’s setbacks up close, Reeves, who had observed mainland Britain’s political tactics, well understood the importance of compromise in politics. He was able to maintain Barbados’ autonomy while skillfully dealing with suzerain Britain’s desire for a confederated union with the Windward Islands. Most importantly he was able to eliminate any buds of the suzerain’s plot of making Barbados a Crown Colony. He also very delicately balanced the needs of the white upper class and the African-non-white class to create the base of three branches of modern government: legislative, executive, and judiciary.

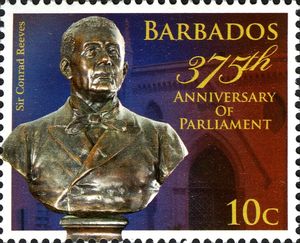

Conrad Reeves was the first person of color to be knighted by the British Crown, and he continued to serve as Chief Justice of Barbados for years to come.

Currently, a bust of Reeves is situated at the entrance of the Barbados House of Assembly. I find it a bit curious why non-white Reeves, whose work greatly benefited the island, has not been named a national hero. This may be due to the fact that his role as balancer forced him to make compromises in favor of the island’s white ruling class.

(Bust of Conrad Reeves placed in the entrance of Barbados House of Assembly)

(Note 1) George Lamming’s novel “In the Castle of My Skin” was skillfully translated into Japanese under the title 「私の肌の砦のなかで」(Getsuyo-sha Publishers, translated by Yutaka Yoshida, 2019). But, the excerpts from the novel in this column are translated from the English original into Japanese by the author (Shinada).

(Note 2) There are multiple Japanese translations of the English term “Crown Colony”. The author has decided upon a set translation used throughout the Japanese version of this volume.

(Note 3) Among the Lesser Antilles islands in the southeast Caribbean Sea, those islands including Barbados which are located in the windward (eastern) side of the trade winds are called “Windward Island”. Other Lesser Antilles, such as the Virgin Island, Navis, St. Kitts, Barbuda and Antigua which are located in the leeward (western) side of the trade winds are named “ Leeward Islands”. The generalization of the terms Windward Islands and Leeward Islands were useful back in the days when navigators relied on trade winds to find their destination, resulting in this seemingly general naming. And just to add to the confusion, the group of islands south of the Lesser Antilles, offshore of the coast of Venezuela, which include Aruba, Curacao, and Bonaire (all of which are overseas territory of the Netherlands), are called the “Leeward Antilles Islands”.

(Note 4) With regard to John Pope Hennessy’s trip to Japan and his letters to his home country, the author referenced Mutsuro Sugii’s “ The Denunciations Against Parks- Some Hints on the History of the Treaty Revision” (1955 Kyoto University Research Information Repository) and Yu Shigematsu’s “ John Pope Hennessy, the Governor of Hong Kong, and Okuma Shigenobu - the Role of ‘Yatoi’ in Treaty Revision and Policy - Making for Okuma” (Journal of Graduate School of Social Sciences, Waseda University, 2006, Vol.8).

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.4.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"416th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.3.13 UPDATE

EVENTS

"415th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.2.20 UPDATE

EVENTS

"414th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.1.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"413th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.1.12 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 15"

- 2024.12.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"412th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.12.4 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 14"

- 2024.11.21 UPDATE

EVENTS

"411th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2024.10.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"410th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"