Barbados: A Walk Through History (Part 15)

Section 8 Trailblazers of Destiny (Cont’d)

(The monument dedicated to the Barbadians who lost their lives in WWI)

The Sugar Industry at a Crossroads

Right around the time when Barbados was able to overcome the confusion of the Confederation Crisis, the island’s economy was in a decline from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century.

The reason behind the stagnation was a slowdown in sugar exports to not only the suzerain Britain but other European countries as well. Since the beginning of Barbados’ colonial history, the sugar industry had steadily expanded and was the pillar of the island’s economy. So why did the industry go into decline? The answer lies with the increased production of sugar beet on the European continent, including but not limited to France, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and Russia.

Sugar beet, which unlike its West Indies counterpart sugar cane, can withstand cold temperatures and thus in the beginning of the 19th century began to be cultivated throughout Europe. In the beginning, imported Caribbean cane sugar was sold at competitive prices and was the leader on the market. However, beet sugar production gradually increased, threatening cane sugar’s hold on the top position.

The increased beet sugar production was a way to use fallow land as well as to protect the supply of sugar even when sea transport was interrupted by frequent outbreaks of wars. In 1863, 95% of Britain’s sugar was imported cane sugar, and 5% was beet sugar. 30 years later in 1893, those numbers reversed to 28% of cane sugar imports, while beet sugar was at 72% (note 1).

Furthermore, in order to protect their beet sugar production, European countries imposed a high tax on cane sugar imports from the West Indies. This forced the decline, starting in 1884, in exports of Barbados’ cane sugar that once accounted for 97% of its exports.

The Rise of the United States and Panama Money

The reign of the British Empire’s supreme rule came to an end in the late 19th century, and the power of United States started to surpass Britain. The United States made its way into Central America, the Caribbean and Pacific region, and Asia. In 1898, the U.S. bumped heads with Spain, the former reign, in the outbreak of the Spanish-American War.

The battlefields in the Caribbean were Spanish Cuba and Puerto Rico. After U.S.’s victory over Spain, Spain was forced to give up Cuba, and Puerto Rico became a part of American territory (The U.S. took Guam and the Philippines from Spain in the Pacific/Asia).

On a side note, in the beginning of the Spanish-American war, when their Atlantic fleets confronted each other off Santiago de Cuba, Imperial Japanese Naval Captain Saneyuki Akiyama watched the battle from the sidelines as a foreign military. The knowledge he gained then was used several years later during the siege of Port Arthur (Lushun-Kou, Manchuria) during the Russo-Japanese war.

On the other hand, Barbados received some windfalls from the Spanish-American war. Since sugar export routes from Cuba and Puerto Rico were blocked due to the war, demand for Barbados’ cane sugar increased, allowing Barbados to export its sugar to the U.S. at a high price for the duration of several years.

However, this was a temporary boon. The overall trend was that while Caribbean sugar was being replaced by European beet sugar. Some Barbadian sugar cane plantations started to go bankrupt. Mostly medium-to-small-sized plantations had trouble operating and landowners had to sell their property for cheap prices, forcing many workers to lose their jobs or to take low-paying jobs.

The situations were similar in other West Indies colonies. As such, in 1902, the British government granted financial assistance to each of their colonies. But, the £80,000 allocated for Barbados was only a drop in the bucket for the island (note 2).

The majority of workers who lost the job were of African descent. Many of them left Barbados to find work in countries such as Cuba, Puerto Rico after the Spanish-American war, the United States, Central America, Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana.

During this period, Panama accepted the largest number of Barbadian workers.

In 1903, the U.S., under the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt, forced the Republic of Panama to become independent from Colombia and subsequently gained the lease rights to the canal zone as part of its plan to build a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In the following year, the construction of the Panama Canal began, requiring a massive number of construction laborers.

Manual laborers from a wide range of countries and regions were recruited to help build the Panama Canal until its opening in 1914. Approximately half of these were migrant workers from the West Indies, in particular Jamaica and Barbados. Approximately 60,000 people came from Barbados looking for work in Panama, which was roughly one third of the population of the island at that time.

The working environment at the construction site of the Panama Canal, which was built with American capital, was not only physically dangerous, but a significant number of workers died of tropical diseases such as malaria and yellow fever. Among the Barbadians who went to Panama to work, some went back home after the completion of the canal and others remained in Panama. The money that the migrant workers made risking their lives on the site -“Panama Money”- that was either sent back to family and relatives back home or kept with them greatly benefited the stagnated Barbados economy.

In George Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin which I introduced in the beginning of Part 8, he touches upon migrant work in Panama.

There was a respected elderly couple in the village where the main character lived.

>> Once a week, on Saturdays, the old man went to town to collect their pensions which amounted to a few shillings a week. But the goat gave milk, part of which they sold, and the pigeons were always breeding. They seemed quite healthy and always looked quite happy except when there was some calamity like the flood…<<

The elderly couple were currently living a quiet life in the village, but the “old man” had 30 years previously been to Panama as a migrant worker.

This is their conversation.

>> Old Woman: “You only got to think back a bit on yuh past, Pa, an’ ask yourself on yuh heart of hearts if it ain’t true. You wus well off once, Pa.”

Old Man: ‘Tis what I says sometimes to myself. Sitting here and there it come to me how things make a change. Time wus when money flow like the flood through these here hands, money as we never know it before. We use to sing in those times gone by ‘twus money on the apple trees in Panama. ‘Tis Panama my memory take me back to every now an’ again where with these said hands I help to build the canal, the biggest an’ best canal in the wide wide world. Me an’ me sister dead an’ gone, God rest her in her grave, an’ as many as me memory can’t hold…”

Old Woman: ‘Tis a next Panama we need now for the young ones. I sit there sometimes an’ I wonder what’s goin’ to become o’ them, the young that comin’ up so fast to take the place o’ the old. ‘Tis a next Panama we want, Pa, or there goin’ to be bad times comin’ this way…<<

Barbados and World War I

Following the boom due to the Panama Canal, Barbados’ stagnant economy received a boost due to the first World War.

On June 28th 1914, the assassination of apparent heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife during a visit to Sarajevo, Bosnia, by a young Serbian patriot sparked World War I. The war pitted the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Russia and others) against the Central Powers (Germany, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Ottoman Empire and others). The war spread across European borders into the Middle East and parts of Asia.

The main battlegrounds of the war were on European soil, greatly devastating agricultural production, including sugar beet. This forced Europe to once again rely on imports for their sugar supply.

Under the above circumstances, sugar exports to Europe from the West Indies received a temporary boom. Barbados was blessed with good weather and a plentiful sugarcane crop during the war, and the sharp increase in exports to Britain and other European countries filled once-empty pockets. Plantation owners who had previously struggled financially to continue running their farms were not only able to pay back their debts, but also had enough money to invest in new machines and facilities needed for farming sugarcane.

The West Indies were not directly involved in WWI. However, a significant number of volunteer soldiers from Barbados joined the war on behalf of the suzerain Britain as it needed all the manpower it could amass. These soldiers were deployed to the battlefields, fighting as members of the British West Indies Regiment.

Looking at photos of Barbadian soldiers in books and historical documents related to WWI, the majority of soldiers were white, while around 20 to 30% of soldiers were Black or non-white. 142 Barbadian volunteer soldiers died in the Great War, which lasted until 1918. A monument was built to honor the fallen soldiers and still stands in the center of Bridgetown to this day.

Activists Wickham and O’Neal

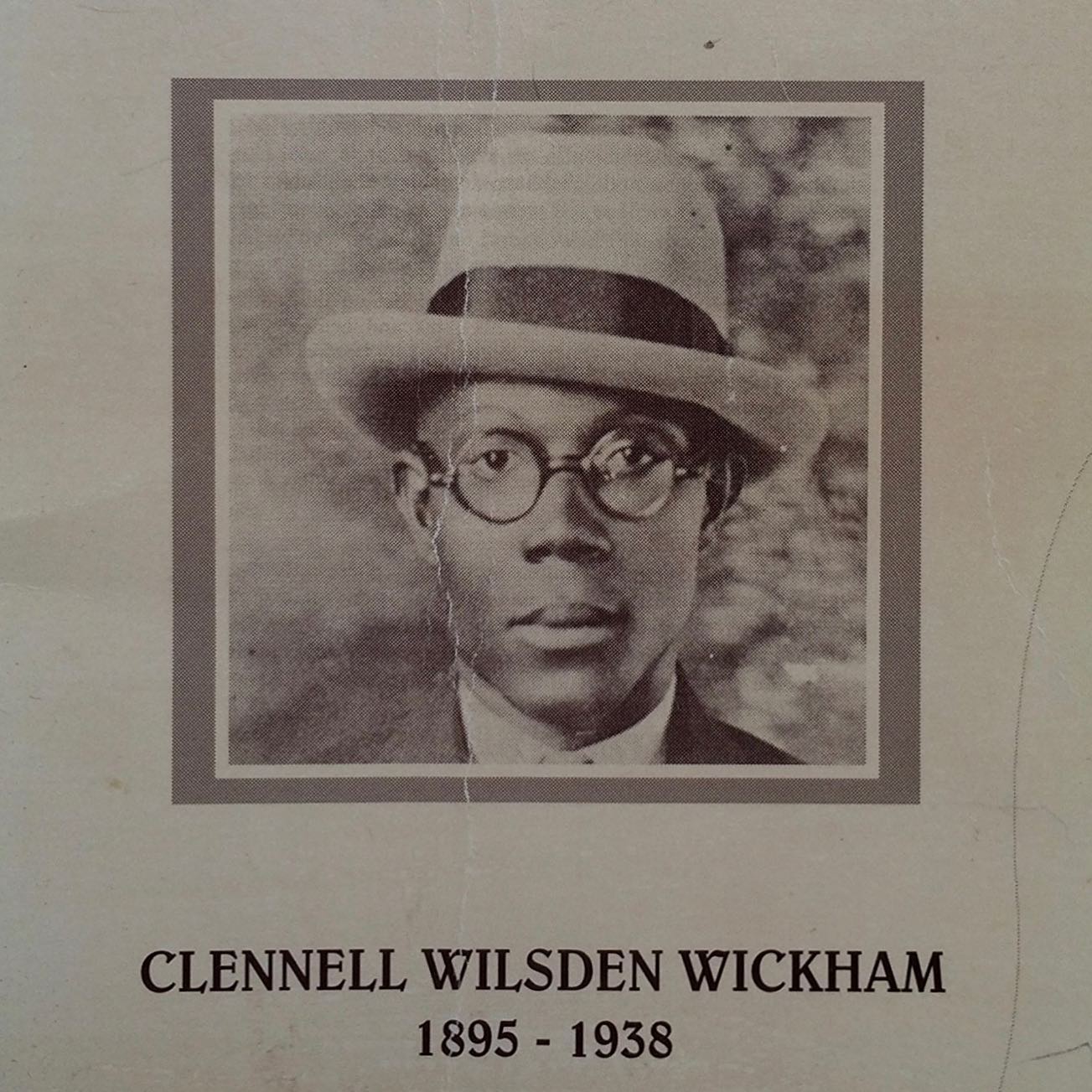

(Clennell Wickham)

(Charles Duncan O’Neal)

Wickham was sent to the frontlines in Egypt and Palestine, exposing him to a completely new world than what he had grown up with in Barbados, a tiny island in the Caribbean. He witnessed the reality that the fate of the people in the Arab world was being tossed about by the big powers such as the British and Ottoman-Turks (note 3). I will omit any detailed explanation of Middle Eastern affairs of this era, but Wickham, who had crossed the seas as a volunteer soldier under the suzerain Britain, came home to Barbados with a new look on the world.

Wickham returned home in 1919, and joined the progressive newspaper “Herald” founded by a man named Clement Inniss. As the “Herald” as his stage, Wickham turned to journalism to speak for the island’s non-white and lower-class population, arguing for democratization and for the correction of social injustices.

Here is an excerpt from one of his writings in the Herald:

(Criticizing the attitude of the Barbadian House of Assembly which pays attention only to the interest of the ruling white planter oligarchy) >> There is no sense of duty to the individual of the island as a whole. There is no sense of responsibility for broad and reasonable treatment. There is merely a sense of class…If the serious-minded people are wise, they will get in touch with the hopes and aspirations of the common people like myself. And find out why we are dissatisfied and what we want. It would be a very dangerous thing if it should become generally accepted that the legitimate aspirations of the working classes are always to be opposed by those higher up. I fail to see why there should be such a hullabaloo because plain John Citizen demands a share in the government.<<

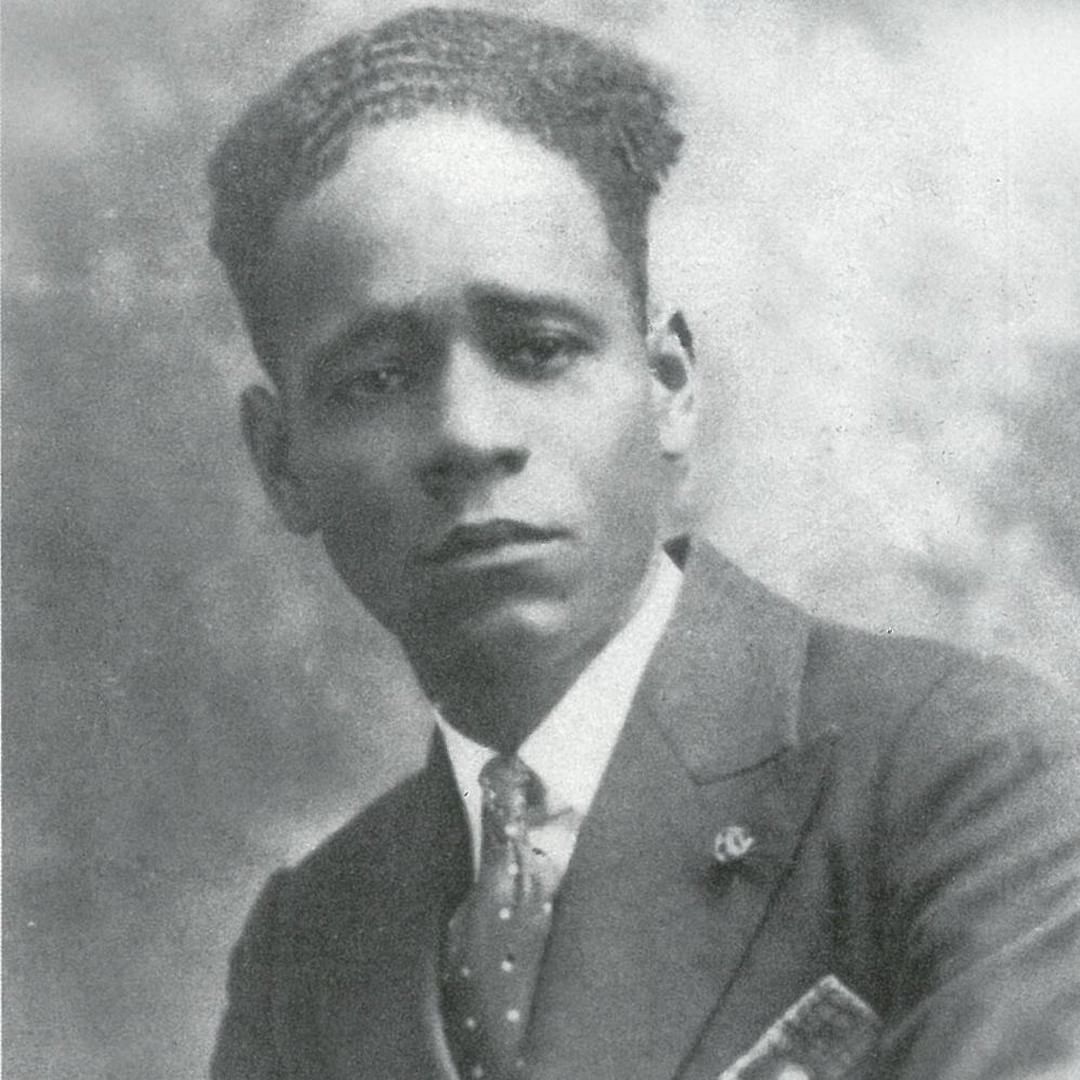

It was a day in 1924, the year that Wickham had made a name for himself as a radical journalist due to his scathing criticism of the island’s ruling plantocrats, when a man by the name of Charles Duncan O’Neal (1879-1936) made an unexpected visit the editorial department of the “Herald”.

Both O’Neal and Wickham had returned safely home after the end of World War I, but each had vastly different backgrounds.

O’Neal came from a comparatively wealthy African-Barbadian family. His father was a skillful blacksmith who opened up his own shop, and was not stingy when it came to his son’s education. O’Neal was a gifted student, and after studying at the elite boys’ school ‘Harrison College’ (note 4) alongside white students, he received a scholarship to the Edinburgh Medical School in Scotland where he attained his degree to become a surgeon.

During his stay in Britain, O’Neal’s interest in politics aroused after seeing first-hand the awful lives of the working class who were the foundation of modern capitalist society. While at university, he became a member of the Independent Labor Party (note 5), and participated in organizing coal miners when he was working in New Castle as a medical doctor.

O’Neal, who had experience with labor union movements in the UK, came back to Barbados in 1924 with the goal of improving rights of the working class, specifically the Black population. It was said that he was disappointed at the lack of resistance and lack of organization on behalf of his comrades. It was at this time that he heard of the many years younger Wickham and visited him at the Herald.

O’Neal and Wickham, who hit it off immediately, gathered like-minded men to found the political group “Democratic League” that year. The tenets of the League included organizing the labor union movement, expanding suffrage, outlawing child labor, making compulsory education free, and establishing a national pension and health insurance scheme. The Democratic League was quick to get a member elected to the House of Assembly-a man of the name C.A. “Chrissie” Brathwaite.

O’Neal had trouble getting himself elected into the Assembly; his first successful election was in 1932. However, his encounter with Wickham and the founding of the Democratic League would be of great importance for Barbados in the coming years. From that time until now, including the period of Barbados’ independence, the island’s political world has been governed by two major political parties, Barbados Labour Party (BLP) and the Democratic Labour Party (DLP), both of which are labor parties. O’Neal and Wickham’s Democratic League was the starting point of Barbados’ party politics (note 6).

the biggest bridge that crosses over the Constitution River in Bridgetown was named “the Charles Duncan O’Neal Bridge” in honor of the mark he left on the budding stages of Barbados’ party politics and labor union movement. O’Neal was also named a National Hero in 1998.

On the other hand, Wickham did not become a politician like O’Neal, but instead he continued to work at the Herald as a journalist, spending all his effort to try and rectify social injustices and protect workers’ rights through his writing. Wickham, ever the idealist, had a tendency to go overboard with his writings, and his articles were often fodder for criticism from the privileged classes.

In 1930 Wickham and the Herald were sued for libel and the paper was forced to close its doors after Wickham lost the trial. Barbados’ society was not yet ready to accept such radical ideas. In 1934 he moved to the neighboring island of Grenada in his despair, where he worked as a newspaper editor. But he passed away four years later at the young age of 43.

(View around the Charles Duncan O’Neal Bridge in the center of Bridgetown)

In the fall of 1929, the New York Stock Exchange crashed, spurring on what was to be called the Great Depression. Its effects were felt around the world, including all the way in Barbados.

The biggest effect was the sharp fall o sugar prices. I previously mentioned how canesugar from the West Indies was undermined by European beet sugar from around the end of the 19th century. This time the appearance of Asian sugarcane on the market forced Caribbean canesugar out of the picture.

Britain’s Caribbean colonies began introducing alternative income-producing crops. For example, Jamaica started to export coconuts and citrus fruits, British Guiana exported rice, and Trinidad exported grapefruits in order to make up for the loss of sugarcane income. However, as Barbados’ available farmland was limited, the development of new crops was difficult, leaving the island unable to wean itself off a monoculture economy. The sharp decline in sugar demand due to the Great Depression hit Barbados particularly hard.

Additionally, the sharp increase in population in the beginning of the 20th century caused a shortage of job openings in Barbados (note 7). Before the Great Depression, it was relatively easy to travel as migrant workers or immigrate to America, Canada, Panama, Cuba, Jamaica, British Guiana, and other locations, thus the shortage of job openings in Barbados was not a big problem. However, the onset of the Great Depression created an overflow of unemployed workers, and Barbadian migrant workers were no longer welcomed abroad.

Barbados was not the only colony suffering. All of Britain’s West Indies colonies were in the same predicament, and rises in unemployment and mass poverty were striking. In colonies where the white upper class minority were in control, things such as party politics and labor union movements were under-developed. It resulted in the lack of a social mechanism which picked up the voices and demands of the majority of non-white and low-income class helping coordinate the interests between workers and managements.

Riots started to occur in the late 1930s all over Britain’s West Indies colonies as dissatisfaction among the masses started to boil over due to the above circumstances.

The first unrest to break out was a general strike started by agricultural laborers in St. Kitts in 1935. A month later oil field laborers in Trinidad embarked on a hunger strike. Large demonstrations and protest rallies followed in British Guiana, St. Lucia and St. Vincent, with clashes between protesters and police occurring in some parts.

The large inequality gap between rich and poor in slave-built Caribbean colonial society caused conflict between the classes to lead to conflict between the races. Thus, the ideologies at the heart of the riots and rallies were, in addition to the political-social ideologies of trade unionism and socialism, the pan-African movement and Back-to-Africa movement, of which Black nationalist ideology was dominant.

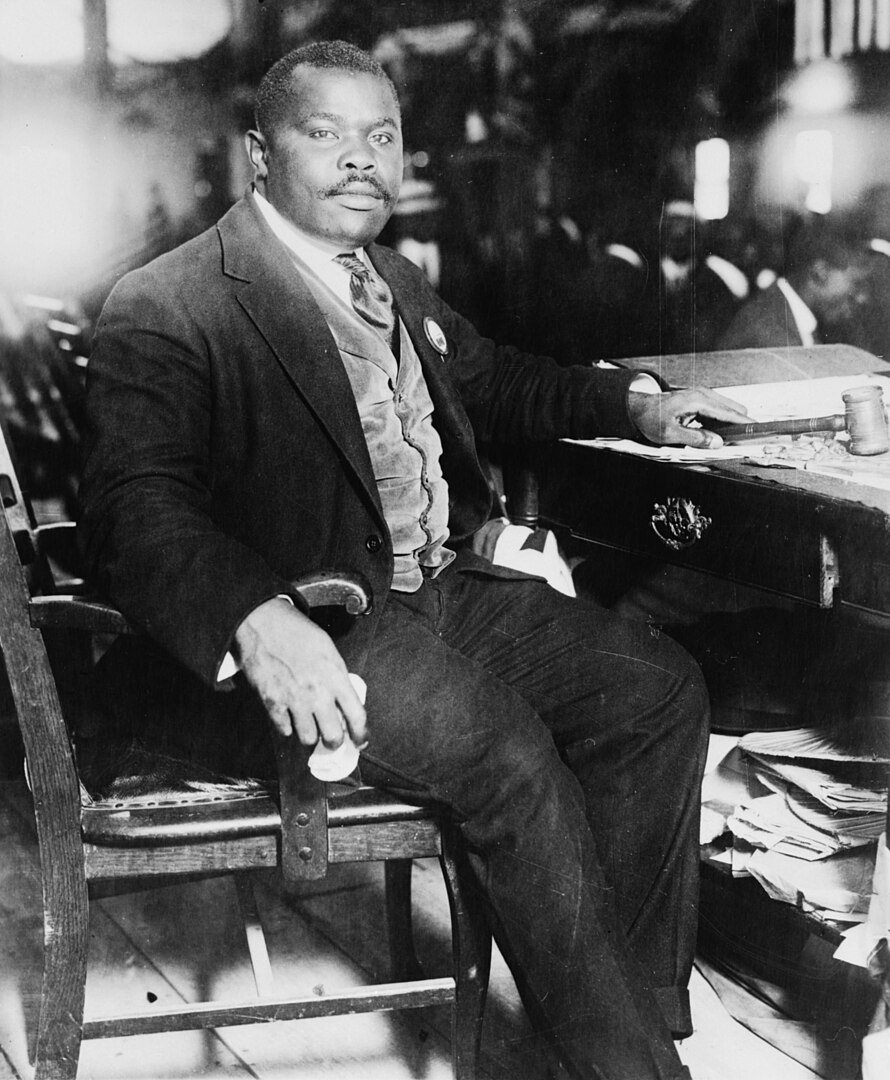

One of the main representatives of Black nationalist ideology was the Jamaican activist, Marcus Garvey (1887-1940).

Garvey’s movement harshly criticized white invasions of Africa, colonialism, and racism. His movement reached across the Caribbean, making its way to America and Europe, even spreading across the homeland Africa, exerting its influence on a world-wide scale. Garvey established UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association), and in 1920 its first international conference was held in Madison Square Garden in New York, where an audience of 25,000 people gathered to listen to Garvey’s speech (note 8).

(Marcus Garvey)

It was not until 1937 that waves of unrest, which had spread over the Caribbean and had their roots in the Pan-African feeling, such as Garvey’s movement, along with frustration at high poverty rates and social injustices of the Black working class, reached Barbados. In July that year violent riots started to break out across the island.

The activist Clement Payne (1904-1941) ignited the riots, which came to be called the “1937 Riots”.

(Clement Payne)

Payne talked about himself during this period as follows:

“It was not long before I became known to a number of persons some of whom remain my dearest friends up to this day. Moving then in a circle of young ambitious men and women I quickly realized the time when I would get into my own. This was no vain belief nor idle thought for just about this time I was attracted by the activities of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, where I was privileged to make my first public appearance and addressed a composite audience of about three hundred persons.” (note 9)

When Payne returned to Barbados in March 1937, he had already become a well-known activist throughout the English-speaking West Indies.Payne’s eloquent appeal for improvement in the status of workers, expansion of suffrage, and the correction of race-based social injustices at meetings held throughout Barbados garnered him tremendous popularity among the island’s Black population, gaining him the nickname “shepherd”.

Naturally, this rubbed the nerves of the white ruling class and the colonial authorities the wrong way. To the conservatives on the island, Payne was nothing other than a dangerous soap box orator who was shaking the foundations of the island’s ruling order.

On July 22nd the same year, Payne was fined by police for “falsely stating his place of birth upon arriving on the island”. As previously mentioned, Payne, who had been born in Trinidad to Barbadian parents, declared his birthplace as Barbados upon entering the island.

The following day Payne, as retaliation for harassment by local authorities, led a group of protesters to the colonial government building. A skirmish with the police ensued, and Payne was arrested and sentenced to be exiled from the island. Payne’s followers demonstrated for days against his expulsion.

A young attorney of African descent, Grantley Adams, represented Payne as his attorney during this time. Adams argued that it was not inconceivable that Payne, who came to Barbados at the young age of four, was raised thinking he was born in Barbados. Despite Adams argument, Payne was deported to Trinidad on a ship and officially exiled from Barbados on July 26th (note 10).

Public dissent came to a peak after Payne’s expulsion, erupting in the “1937 Riots”. In the evening of this day, a protest in support of Payne was held at Bridgetown’s Golden Square. Some of the indignant protesters became violent and began damaging whatever stores and vehicles were around them. The number of violent protesters increased to a few thousand in the blink of an eye, and looting started to occur. The police, who had underestimated the seriousness of the situation, were not able to control the protesters. Soon the protest had turned into a full-scale riot.

The riot, which expanded into the countryside, continued into the following day and was finally suppressed by an armed police force, leaving 14 dead and 47 injured, and several hundred people arrested. The riot left its mark as being the most violent protest in Barbados modern history (note 11).

George Lamming’s “In the Castle of My Skin” describes experience of the 1937 Riots by the protagonist, actually the young Lamming himself, in the following manner:

The riot in Bridgetown had made its way to the village where he lived.

>> All the shops were closed. The school was closed. In the houses they tried to imagine what the fighting was like. They had never heard of anything like it before. They had known a village fight, and they were used to fights between boys and girls. Sometimes after the cricket competition one village team for various reasons might threaten to fight with the opponent. These fights made sense, but the incidents in the city were simply beyond them…They were fighting in the city. And the fighting would soon spread to the village. That was all that was clear. And they couldn’t say they understood that…<<

Afterward, a part of the rioters entered the village and marched up the hill to attack the “enemy of the people” --, the aforementioned white landowner’s estate. The story comes then to a nail-biting turning-point. (I wouldn’t want to give away the ending.)

Disorder in the region continued even after the Barbados’ 1937 Riots. In the same year, a large-scale labor strike occurred in British Guiana and St. Lucia. The rebellion in Jamaica the following year in 1938 where a general strike led to violence and death was the pinnacle of turmoil in the British West Indies.

The British government, who took the incidents seriously, set up a commission to investigate the cause of the string of riots. The commission came to the following conclusion on the Barbados riots:

“There was a large accumulation of explosive matter in the island. The Payne incident only acted as a detonator. The real cause of the disturbance was not political agitation but the harsh realities of the economic situation facing the people.”

We have to hand it to the Brits to make such as a cool and collected response to the fire burning at their feet.

Nonetheless, about a century after the British abolition of slavery, nobody could stop this movement of racial awakening all over the West Indie, including Barbados.

*********************************************

The Second World War broke out in Europe two years after the 1937 Riots in Barbados.

The main character in Lamming’s novel continued on to high school after graduating elementary school. His was a rare case in the non-white village. His neighborhood friends went straight to work or gain passage to the U.S., relying upon relatives there, after finishing elementary school. But the protagonist, an honor-roll student thanks to his Mulatto mother’s passion for education, received a scholarship for high school.

One day, a man visited the headmaster’s office of the high school.

>> One day shortly after lunch a young man called Barrow walked up the school yard and entered the headmaster’s office. He smoked a cigarette as he spoke to the headmaster, and one or two boys who passed by the headmaster’s study stole a glance and ran to inform the others. Some of them said they had known Barrow at school and it looked strange to see him smoking in the headmaster’s presence. We were a little curious. In the afternoon the school was assembled and the headmaster talked about Barrow. He was leaving in a fortnight to join the Royal Air Force…<<

The name of the high school in the novel is not revealed But there is no doubt that the school, Lamming’s alma mater, is Combermere School. This school is Lamming’s alma mater, and the man who visited the headmaster had also once belonged to the same school.

The man who conversed with the headmaster was an actual person named Errol Barrow. If my math is correct, he was still a young lad of 20 years or so (note 12). Barrow was the nephew of Charles Duncan O’Neal, and he did in fact actually join the British Royal Air Force, and was a rare Black crew of fighter aircraft during the war.

As “In the Castle of My Skin” was Lamming’s autobiographical novel, many real-life figures made an appearance in the story. However, very rarely did Lamming use real names; the majority either do not come up, or he used fictious names. Lamming’s use of Barrow’s real name is an example of rare instances in this novel.

Errol Barrow, the man described in Lammings work as a “man with a big attitude smoking in front of the headmaster” returned to Barbados after WWII. He would go on to play a pivotal role in the movement towards Barbados’ independence, alongside Clement Payne’s attorney Grantley Adams.

George Lamming, whose life the main character’s story was modeled after, continued to publish novels, poems and essays after his autobiographical novel became famous in Britain. He also taught literature at universities in America, the Caribbean and other part of the world, cementing the influence as a prominent figure in the modern Caribbean literature. In his late years Lamming returned to his homeland Barbados, and in 2022, at the age of 94, took his last breath.

(To be continued in Part 9 Trident’s Promise & Independence)

(Note 1) “Barbados A History from the Amerindians to Independence” F.A. Hoyos, 1978, P.173

(Note 2) Barbados at this time received financial support from the suzerain Britain’s Secretary of State for Colonies Joseph Chamberlain. One of the two bridges that cross the Constitution River in central Bridgetown was named after Chamberlain, and bear his name to this day. Chamberlain Bridge is a swing bridge that lets water traffic through.

(Chamberlain Bridge runs across the Constitution River)

(Note 4) Harrison College is the descendant of the formerly all-boys Harrison Free School (secondary education) established in 1733. The school, alongside the formerly all-girls Queens College which evolved from the Central School established in 1819, are the two most prestigious secondary schools in Barbados (both institutions are now co-ed). In addition, the Lodge School which branched off from Codrington Grammar School (see Part 7 for reference), and the famous singer Rhianna’s alma mater Combermere School are also notable secondary schools on the island.

(Note 5) The Independent Labour Party was a political party established by the Scottish Keir Hardie in 1893. Following its establishment, the Party united with the Labor Union, together with the Social Democratic Federation and Fabian Society, eventually becoming the Labour Party.

(Note 6) From the beginning of political rule in Barbados, the influence of social democracy, such as labor union movements, Christian socialism, Fabianism. which relied on British labor parties, was strong. Communism and Marxism, which placed importance on class struggle theory, never took a hold on the island.

(Note 7) For example, according to “Barbados A History from the Amerindians to Independence”, in the 1921 census the population of Barbados was 156,312; however, in 1937 the number had risen to 189,350.

(Note 8) Marcus Garvey’s ideologies influenced the following Rastafarian movement and the Black Civil Rights movement. His name even appears in some Reggae music as well. In his later years, during a tour of the Caribbean, he visited Barbados a mere three months after the 1937 Riots. During this visit he gave a speech in Queens Park in the outskirts of Bridgetown, which drew in a large audience. In 1964, the Jamaican government elected him a national hero.

(Note 9) “My Political Memoirs of Barbados “ by Clement O. Payne

(Note 10) Clement Payne continued his work in Trinidad as an activist for the labor union movement. However, he passed away four years later at the young age of 37 without returning to Barbados. He was named a National Hero of Barbados in 1998.

(Note 11) Later a building was constructed in Golden Square in central Bridgetown, where the 1937 Riots had started. However, the building was torn down due to age, and the area was reopened with the new name “Golden Square Freedom Park” a few days before November 30th, 2021, when Barbados transitioned from a British Commonwealth Realm state to a Republic. I had the honor to be invited to the Opening Ceremony of the new park. When I caught a glimpse of a large bust of Clement Payne behind Prime Minister Mia Motley, who delivered a speech stressing the meaning of the 1937 Riots as Barbados’ departure point in the fight for freedom and independence, it reminded me of the role that the riots played in modern Barbados history.

(Golden Square Freedom Park, the location of the 1937 Riots)

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.12.25 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 17"

- 2025.12.2 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Pacific & Caribbean Student Invitation Program 2025"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Support for the 2025 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Invitation Program for the Director of Bilateral Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Jamaica"

- 2025.10.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"421st Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.9.18 UPDATE

EVENTS

"420th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.8.28 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 16"

- 2025.7.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"419th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.6.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"418th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"